On a Wedding in Mariposa

… in the wilderness of Amerika

I have seen first visions, chosen

a name and a calling

of change, returned to learn

to bring together brothers and sisters

to midwife the uncertain birth

of our longing. And today,

as the first men streak

to circle the moon, on the first

day of Winter in my twenty-ninth year,

I have taken an helpmate, she whom

all my life speaks

but my song, wordlessly

sealing this time with a stone

of topaz found on a dusty road

half a life back in the map

of a name, and always held

in reserve, awaiting

a day of the choice

of the heart's society.In the background,

in the perpetual process current

that mirrors the stream of our

difference and change, the Beatlebirds

sang take those broken wings

and learn to fly. And her face

lit inward, as she fell

to her knees against me,

and we stood there in softness

and stone, trying to sort out

the colors of that flash.I do accept that tragedy

will flower through us in

its ripe young time.

Yet still am I filled

with a thin singing,

that translates its yes

fearful of flesh through these

sentimental and shaken lines.21 December 1968

Midway between Chicago and People's Park we married invisibly in a Berkeley party, months later chose to make a public ceremony of our affair.

There were seventeen different kinds of flowers in the meadows, live surf breaking across the great rocks we chose to marry upon, streamers and spray curling our feet. I counted them, floating above them, mind whirling, bee wild with the rich stink of spring. Some I knew, wild iris, shooting-star. Others, like the massed strawflowers toe-high and tangerine yellow, I'd only met at times before and never learned their names. And here all came together, to grace the theater of our wedding.

We invited the people we love, the friends of our family, our lives -- how can I name the common denominator? The young professionals: social worker, teacher, physicist. Dope dealers, film makers, painters, our ex-students and lovers, comrades from eleven years of politics and life in Berkeley, sociologists, parents, millionaires and mediamen, beloved freaks from the Common Street. Most like we were late twenties, give or take. My parents were there and a handful of older others we prize, and eight small children who roamed the meadows in a pack gathering nosegays.

We brought all together on friends' land in the Sierra foothills, above Mariposa. Huge house, cottage for us, pool blasted out of the granite and warmed for the occasion, and eighty rolling acres of spring country -- oak, pine, and private, away from strangers and the police. So much of what unfolded was permitted by that land, and enabled by the warmth with which Danny and Hilary opened their house and helped care for the hassle. Free space, only four hours away from Berkeley! About a hundred of the 160 we invited made it. They brought maybe twenty kin we didn't know, sleeping bags, playthings and presents.

People started showing up on Thursday, came in all the next day and the morning after. Up the alarming road, park the car, find a place for stuff in the house, gossip and smoke some dope in the kitchen, from the open bowl with a clean pound of gold. Then lovers off alone, barefoot through the unbelievable meadows. It was like that; Saturday noon you couldn't go fifty feet in the upper meadows without stumbling on some couple coupling. They'd wave lazily, and later drift down to the crowded pool, where people mostly new to social nudity were mostly lying naked, ehattering across microcultures or sharing the vibes like sunflowers under the benediction of the light. In the water the children played cooperative games, like trying to keep an air-ball in the air.

Karen and I were clear about the context we wanted. Some months before we'd reached another plaee of decision and beginning, involving confessions, time, and a child. We dealt with it privately, but no life can be private now and free: and we wanted to make a public completion, a ritual of our choice to move on together. First we planned to do it in March, but by M-Day-minus-7 two feet of snow were still on the meadows. So we called everyone to say, "Cancel, we'll tell you when." There was no rush, after living seven years together and breaking up three times forever and all the changes in between, and we wanted everything to be right. So we waited till after the weather warmed, late April.

We had two ideas. One was that we wanted to be married in our society, not the old one. We are each bummed by legal marriage, which exists primarily to define each other, the goods and the lids as property. It's hard enough understanding who we are and each other anyway which is why, with twenty ULC ministers beside me there, we still didn't choose to make it "legal." But what do we want marriage to be in our society, in which we are learning to share much that was private -- our lives our love our children? Karen and I are still just beginning to create new terms. We wanted to confess our experiment in all we knew of home and a public, the society of our friends. And we wanted all to share in creating the ritual, for we are all involved in creating the terms. This was the other idea: that we wanted a coming-together not of us before an audience, but of us all.

Beyond these thoughts and arranging how people would eat and sleep, we had made no plans for our wedding. We were easy with this as a matter of principle, besides which there was no time: I'd just gotten back from the Midwest, a week's heavy work in a huge dorm complex with a swarm of twenty migrant ed reform workers. That was an historic engagement, the first time Women's Lib brought everything to a grinding halt in a national gathering of the ed reform movement. Six-hour fishbowl, lots of fallout and unresolved anger: as a heavy male agent, I caught at least my share. A weird preparation to marry with a woman, sort of like cleansing by fire. I came back raw and tight, pissed mainly by our work's getting blown. Karen was furious at her sisters for their timing. But it was high time. I saw us caught in the river of history, trying to learn to go with the whirling current. So much is happening, no time to move by plan, maybe enough to relax with, play it as we go. We drove on up to Mariposa drinking chocolate malts at the ratburger stands, sharing them with the dog, and as the Rambler straddled ruts up the last stretch she told me how the women had worked weekends with the men to repair the road's winter ravages: rock hard in their hands and their breasts bare to the wind and sun and the stone face of the neighbor who passed in his jeep.

For four years, with a growing web of friends in work, I'd been learning how to design events to bring people together, to create about their needs -- politics, learning, festival -- in deliberate painful experiments, here and there on the road. Many l'd worked with were part of the wedding. It was as if all we'd learned about how to do it went swiftly and naturally into action through us, just by our letting go. Karen wandered, determined to say yes whenever anyone asked her anything, opening situations. "Other than my role and love," she says, "1 saw that as my prime gift input into making the magic/whole."

No plans. Help your people come together: that is the first principle. So we got the best environment we could, and left people free to do what they wanted. Most got a day and a half to sink into the woods and each other before anything "happened." It was heavy, seeing how free space and open time made people feel they could go off alone and still be part of the whole. Few there knew many others; they moved in and out of the gathering places bright with first contact, meeting kin known by name or mutual intimacy: the divided energy-centers of our generation, coming together.

Surely the acid helped. (An old student brought it with special pride and wholesale.) We'd only recently dug that acid helps heavy group-synch things to happen. This was an exceptionally mellow batch, so mild some took four. Only eighty caps went over the whole weekend, but between that, private stash, and general relaxation, by Friday night the vibes were so dense there was no one left to catch contact high. Save a few in private sorrow.

That night in the cottage, candles and fire and musicians and wine. Carl Oglesby came down from Oregon, fresh from his first paid performance as a singer, and for a long time sang to us of our lives. Can I tell you it was magical? "A child's idea of happiness," he sang,

reminding us our crime was very old,

the ancient tales suddenly grew strange

lovely children passing into exile

had left us unknowingly changed …

And later, not quite believing our surrender to longing, we sang as his chorus:

Che, Che, Che,

I'm calling your name, Che, Che,

I'll find my Sierra one day,

I'm coming your way ...

Late Saturday morning people were digging the pit and chopping wood, or making music. We'd asked all to bring a cake or bread, thinking to make a mutual cake. We favored a man and a woman, but the children were building. They built their bricks into a barricade and plastered it high with sloppy frosting. Jeanie and Barbara discovered each other while hemming Karen's dress. Dad met Karen in the bathroom pissing and marveled at the cornucopia of tits by the pool, observing that one could do the research of a lifetime there. Outside on the bank Michael Haemowitz was sitting with some people from the Floating Lotus Magic Opera, binding black and white fur to buffalo hoops, practicing ceremonial passes. We took him and got Ken and went for a walk, to talk about myth and ritual and how to divide up the Mysteries.

Sometime that afternoon Karen and I flashed together, looked at each other, and decided it was time. Spitted over the fresh barbecue pits, the lambs had been roasting for hours. We went off to the cottage to plan, giddy with anticipation and mellow purple powder and everyone's touching. An hour and a half later we had the framework of a ceremony and some words to say together. We said them through a couple of times, pretty sloppily, got impatient, and went out to call people together and get It on.

We gathered everyone around the pool, while the last lovers came down from the hill, and set the context. Men and women would go off from each other for a time, to perform two tasks. The men would choose a place for an altar and build it, and find a way to deliver me up for marriage. The women would deliver up Karen, and dress her and decorate the altar. All with as little talking as possible, and without our leadership. In their hands we would come together to say our words. When? 5:32, because it was now 4:32. Right on! and it began.

The altar was of piled block granite and dry manzanita. They built it where the bones of the earth show through in twin granite domes. All the ranch was Indian home, but the domes are special: the top of one is pocked with grinding-pits for the acorns, and walls the Indians built still run across their faces, soft with ferns and lichens, while we try to deal with the guilt of their theft by the uses of love. On the dome the men piled the new rock, and the women garlanded it with pine boughs, roses and a pattern of pine cones focused in a star. They hung the great Yin/Yang banner Barbara made over the central stone, and the children placed their nosegays. Cicadas and guitars swelled in the wind. Someone noticed I was missing and went off to find me.

Apart from my brothers, on some high stone I sat and thought about continuity, felt the warmth of its embrace facing the absolute chill of our leap into unknowable open space. My mother's father was a Bolshevik, fled here from the prisons of the Czar; I have his blue eyes. He married his wife when I was twelve, to settle property rights. My father brought my mother home after their civil ceremony, to make their true vows on the Party Book -- he told me this when I was twentyfive or so, and started to cry. The wind touched me with the cold of McCarthy winter; I grew up waiting for the knock on the door. One with the tree and the branches of manhood above me on the rock, I sat and marveled at how the spirit shifts around down time, from longshoreman to labor journalist to . . . what, technician of learning? I wondered what Karen was feeling, thought I knew, thought of how from the intimate core we've been learning together to honor our fantasies and accept their power, of how we are learning to dream and to live dream out, when dream's agent came to get me.

He brought me to where the men were milling, a quarter mile from the domes. The male dogs had come along, the female were with the women of their own accord. Each man had got himself a stick, of twisted manzanita or pine, and many had fixed lit candles on theirs. They had made a canopy of the bedspread Betty had tie-dyed for us, and four raised its corners aloft on long boughs. They set me under it, bright in peacock blues and greens, in the tunic my sister Leisa dyed in subtle faces and sewed, flapping my wings in embarrassment; I have never felt so purely beautiful. A wordless chanting began, rose up like a sudden dragon. Bass strings and flutes shifted tempo and started to drive. The chanting quickened, fresh with sweat. A procession formed around and behind me, lifting and thumping their sticks, male voices ringing into ragged exultant harmony, and we set off across the open hills.

It was late enough for the candles to show clearly by the time we topped the final rise, long after 5:32. Across the meadow we saw the women approaching in symmetrical procession, in their colors and flowers, leading Karen beneath an ancient tapestry of cock and dragon. The falling sun lit her through a mist of fabric, the subtle greens of new bean sprouts. They too were chanting, softer, silver. Across the domes we heard each other approaching, the sounds swelled as our lines converged, merged and swirled into place around the altar. The chants grew together into a great Om that went on and on and on. And then there was silence, and Karen and I went into each other's eyes in a long moment of total surprise at being there before the stone. Our dogchild Bull pushed up between us, black muzzle briefly touching our crotches, anxious to share some together. We took him in and turned to begin.

"But there are no beginnings, no ends," we said together, facing the circle of our friends around the stone, "that's just the way we speak, helplessly, or we couldn't." Karen went on alone, from an old poem to her,

"When you open to one thing, you open to all,

which is why all lines,

accepted abandoned or longed for,

lead through this time, these selves."

And I said a poem by Robert Duncan that we had shared for years. It appeared with a pop! on the desk one morning when we were talking about wanting text for a ceremony, at a peculiar conjunction of moon, expectation, and a humming witch in the kitchen floating down morning-after mescaline -- by teleportation, as far as I could discover by prying with a mind that was trained for science and has seen such things happen before.

"The fear that precedes changes of heaven

opens its scenes; petal by petal longing

a flower opens; its seeds needs

ong unacknowledged, urgencies

as if grown overnight. These

voyages toward which we find ourselves,

unbelieving, proceeding. Passage

as if of death unfamiliar.

Coasts wrapped in unrealized light right

directions beyond belief where

desire moves us. 0 real mere islands,

new lands, bear with us, allow

for the heart's turning."

We turned to face each other and joined both our hands in a Taoist clasp. Unsteadily I said, "I do not commit myself to the death of property." "I accept you with your body and spirit free," she said, and then, "1 do not commit myself to the illusion of forever." "I accept you open to the changes," I responded. And then we asked together, "What then is your commitment?"

"To have you take me with all that you know of seriousness," answered Karen, "and celebrate me with all that you know of joy, in the process of our becoming the world which we conspire."

"To have you walk with me as the woman of a poet and a pioneer," I answered, "and face Death as guerrillas of Life in the jungle of Amerika."

"I accept you as the father of our child," she said.

""I accept you as the mother of our work and life," I said.

We raised my Mother's gift goblets of May wine to each other. Karen flashed that with them in our tunic and gown we struck the icon of the Two of Cups, which long before she had seen as the card of our marriage. A winged lion's-head rose from our hands, above the healing serpents. We tipped and sipped the goblets and started them passing from hand to hand around in the liquid circle kiss. And then shrugged, and said in unison into the lingering silence Karen's favorite line from Joyce: "Well, as well you as another," our most cogent vow, and dissolved in the sacrament of laughter, digging the stunned moment before everyone joined.

When it settled we faced them again and asked them to speak words with us, grown from a ceremony we improvised early that spring at Iowa State. I said a line and the men said it back; Karen said a line and the women responded.

"The endless journey has slowed to halting."

"The end of the circle is the beginning."

"The ancient image has lost its splendor."

"There is a circle whose center is forming."

The women's voices were light in the reddening sunset, the men's were like earth.

"We are a question not yet framed."

Karen and I spoke the last lines together, and we all repeated them, one by one:

"The titles we bear form weary rhymes.

"I have a name no one has spoken.

"We have a name no one has spoken."

After the silence we called the space open. George, another love once student, read the poem he had written for this time:

A falcon circles with his eyes

flying in rhythm with the sun

a serpent coiled around his legs

sliding dark

brings round the circle.Raised out of moisture

in an age of metallic fire

dionysios gushes forth in bodies

breathing into streams of crayfish

playing in a sparkling spot near bottom.

Erasing the shadow of his mother

the spider of us all

he clears webs of repression with splendid nakednesssoothing a flame to life

surrendering when not attacked

comforting when nothing is lost to share and not to own.

Then Karen chose to throw the I Ching -- we hadn't planned it, she's the custodian, when the spirit moves her. I was so spaced out by then I didn't realize what was happening till I came to with her hands guiding mine through the even tosses. The coins clinked on the stone. After the last toss she went into a huddle over the book with her occasional lover David and girl friend Barbara, while we waited for them to take turns reading the judgements.

The first hexagram was I, Increase. "Increase," read Barbara, "it furthers one to undertake something. It furthers one to cross the great water. Sacrifice on the part of those above for the increase of those below fills the people with a sense of joy . . . When people are thus devoted to their leaders, undertakings are possible, and even difficult and dangerous enterprises will succeed. In such times of progress and successful development it is necessary to work and make the best use of the time. This time resembles that of the marriage of heaven and earth, when the earth partakes of the creative power of heaven, forming and bringing fonh living beings."

"Aaah!" cried Stefan, the Savios' three-year-old son. "Aaah!" responded everyone in low wonder. "Aaaah!" cried Stefan after a moment, probing. "Aaaaah!" we cried, building our fantasy together, and he led us on and on in Aaahing until the pure sound of astonishment climaxed, broke, and subsided. Then Barbara finished the judgment: "The time of INCREASE does not endure, therefore it must be used while it lasts."

The fifth line was moving. and the hexagram turned to I, The Corners of the Mouth. The judgment: Perseverance brings good fortune. Pay heed to the providing of nourishment, and to what a man seeks to fill his mouth with … If we wish to know what anyone is like, we have only to observe on whom he bestows his care and what sides of his own nature he cultivates and nourishes. Nature nourishes all creatures. The great man nourishes superior men, in order to nourish all through them.

Kneeling over the stones and its garlands, distracted, a candle caught Karen's hair, quick fingers flickered up half its length. She is terrified of fire, has nightmares of flame death. In the dreamslow motions of acid or ecstasy, mindless, I reached out and disappeared the fire. She didn't notice till it was all over. Then we clung to each other, shaking. Heavy icons, golden haze, the universe slipping in and out of focus. Twilight fell. We scattered over the hills, Karen and I wandering homeward clasped in anonymous silence. By the fire I ate from the lamb, didn't see her leave to go upstairs. In the basement Marilyn and Adrian labored over the cranky woodstove, discarding batch after batch of brown rice in search of a little perfection. Transfixed by the omen of flame. Karen huddled under the covers. For the only time that weekend I called her from afar, "Hey, McLellan, McLellan," and she came down out of blackness into the warmth of the living room, where some were making music before the fire. And then the fantastical candles were lit, and the children's great barricade cake unveiled with its freaky frosting. And then upstairs the sharing of gifts continued.

It is harder to take as property artifacts seen to have lives of their own. I can't list all that was shared with us, play of the Children of Affluence with their tastes gone all peculiar. The refinished Goodwill rocker, the ceramic plate with a Tao of flower fields and stars, the elaborate amp and tuner, the great pillow sewn of chamois squares, the boxful of strung eucalyptus nuts, the Masai warrior wedding belt, the jar of unpoisoned morning-glory seeds, the patiently fitted crocheted lace dress, the enchanted box sent by our Illinois family, the bundle of lacquered yarrow stalks, the poster from a community strike, the paper icons and fantasy objects. The work of our hands and our hunting and play, show of affection in an open place made together. In the weaving light another Michael charmed Karen into dance with his fingers full of oranges and laughter. And later Tarney took me off and washed me with gentle hands, dried me in rough terrycloth, held me till my blood rose up, and we touched and she sent me off to the cottage. Only the ghost of Carl's singing lingered. The dog curled up before the fire, and Karen took off the wedding belt and we made slow lingering love, a little shy and a little sad with those outside who were still outside what so many had come to share together.

Do you see? Karen complains I write this as history, the magic slips through. I want to cry out: such are our people, this is how rich we are, here is a tangible sliver of how we are learning to shape and share our love. For this was half and more why we chose to make a public thing of our marriage: the sense that all around us were filling slowly with a strength of joy whose size was still unknown, because we hadn't yet gone beyond demonstration and be-in in inventing the forms that will show us what we are becoming.

We wanted to be an excuse, an occasion to focus our energy within and beyond the unending War. Karen saw us as a sacrifice, in risk and experiment; and like the wedding couple in A Midsummer Night's Dream, "as if we were presiding somehow, both cause and irrelevant to the magie ... The mellowness and freedom were a light of 'could be' at the end of dark 'what is.'" Me, I see us in history. We brought the best people we know together in a ripening time, and it happened. From that event lines of energy run out through many people's lives.

Long after, friends were still telling us how they felt everyone actually married there at Mariposa. I lost count of how many couples confessed how it had brought them tegcther. When she got back to Berkeley, Ann wrote us to say this of her and Ray, and more: "I had never seen the children act like that in public before, so peaceful ... After we came down we went to People's Park and stayed there a long time. Michael, it was like the wedding, only larger, with black people and old people and hippies and plain housewives like me. I have never been political, but I know now that if they come to bulldoze the park I will be there with my children, up in front of the blades ... "

Karen and I hung out in Mariposa alone for a few days after the wedding, letting it sink in with sun and psilocybin. Then we cleaned up the house and took off for Reno with Bull. With Tom and Russell in a pack we blew an NSA regional conference on ed reform to pieces. In the wreckage Karen and I asked people what they wanted to deal with, found it was sex, and pulled together the first version of the extended workshops in sexuality and learning, sexuality and politics, that have been the focus of our growing work together this past year. The Reno shot was our first formal work, first try at converting to teaching what we had learned in the past seven years together. Fit honeymoon.

That was a rising spring, latest of a sequence of many, rich with parallel journeys; so many people treading the common road of changes, quickening. Bad omens in the sky, since long before Chicago visible in Barometer City. When we got back to Berkeley from Reno, the Park was a legend of life, a free place where everything we embrace converged. Two weeks later the Park was a tundra, encampment of soldiers and pivot of helicopters, and Berkeley was an occupied city, five thousand in the teargas street. We went all together from the three houses we share, little Debbie cried because we wouldn't let her come: "I'm old enough to run." Running in the street, I saw people who met at the wedding move together under attack. Got separated after the women went home, when the shooting started. Running down Dana, one birdshot pellet hit my left thumb, an icy sting. Left a tiny black spot that lingered for weeks, bit of dead flesh in live, just the size of a literary grace, like a period. It started me writing the longest and heaviest poem of my life, trying to put it together, about the wedding and the Park and that little black spot.

Now Rector is dead on a Berkeley roof, and Hunter is murdered at Altamonte, and the Eight have been racked in Chicago. Our child was conceived in the back seat of a car on the road to El Paso to do our second piece of work together. It is due in mid-May, I am building a nursery for the child and the ferns, we're wondering how the dog will respond, and preparing to change. A year now since the wedding, I look at its terms and description with altered eyes. They seem to me much more clearly sexist than I'd even feared then. Or maybe not, for I'm a poor recorder of the mark of Karen's spirit on things, and I've learned that her terms work in me and around us long before I can recognize them. Whichever, we've attempted a division of the Mysteries, and if it isn't in harmony we shall try to begin again. Last month we got back from a month on the road, working together, big belly and all and the dog. Most of the campuses we stopped at were recent with conflict or about to blow. All our friends and the people we worked with were going through heavy changes, uncertain as hell but moving on as fast as they could manage. Back in Berkeley the Free Bakery has opened, capacity 2,000 loaves a day. Reagan is calling for a bloodbath. A thousand tenants are on strike. Nixon says to safeguard civil liberties the dangerous ones must be identified. Here we are planting gardens. I started to write this in Mariposa. While I've been finishing it in Berkeley someone's blown up the power line to the Radiation Lab and campus. As I write these words the plazas and streets are thick with CS gas, a thousand have taken refuge in the Student Union, the Chancellor has declared a State of Emergency, it is sunset, 15 April 1970. I sit on the porch and play on my guitar, learning to sing while we wait for the baby.

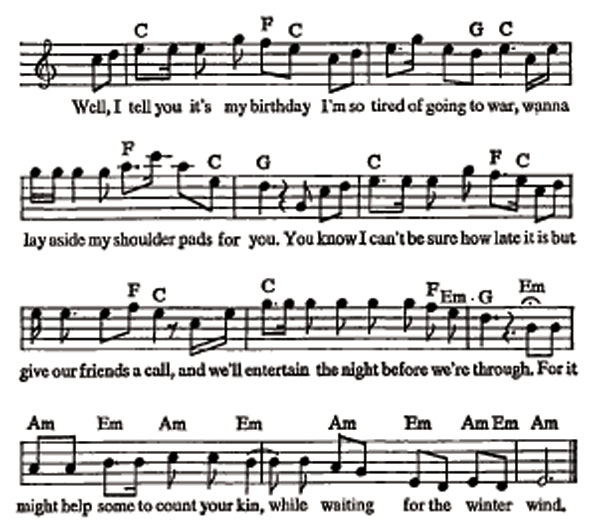

Well, I tell you it's my birthday

I'm so tired of going to war,

wanna lay aside my shoulder pads for you.

You know I can't be sure how late it is

but give our friends a call,

and we'll entertain the night before we're through.For it might help some to count your kin,

… …Oh, I met you on the picket line

when we were decade young,

singing, "We shall overcome ... ,". (*)

and we read each other's leaflets

in the lonely downtown rain

and I said I'd trade you coffee for your name,Thinking it might help some to count your kin

… …You were trying to write on granite

as we sat there in the hall,

a fingertip was all you had for pen,

crying "Power to the Pipers!!"

as we waited for the dawn

and the hoofbeats of the Sheriff's Highwaymen.And it might help some to count your kin,

while waiting for the winter wind.They were selling plastic sideburns

when I met you on the green,

come to count the birds that everyone became.

When you asked how many made it,

I could only tell you why

and dance with you the sacramental hour.… …

While waiting for the winter wind.In the streets the fog is angry

where the nimble speed the lame,

you have pulled me from the clubs of our despair.

Mind if I sit here by your campfire?

it might help to clear my eyes,

we'll play boyscouts out to brave the wilderness,For it might help some to count your kin

while waiting for the winter wind.And I don't know where the rain falls,

but I know the reason why,

how it wakes the seeds to struggle underground.

And I've seen the way the heart works,

how it waits to claim its time,

and it beats and beats and beats a man to death.So it might help some to count your kin,

while waiting for the winter wind. (repeat)