The Fourth Night of Cambodia

The night we named our child we had fish for dinner.

"What shall I do with the filet?" asked Karen from the kitchen, "there are bones in it."

"Cook it," I said.

"I don't like it with bones."

"They come out easier after it's cooked. That's the way fish are."

"Oh, never mind." Clatter of pans, water running. Indistinctly: "Screw you, anyway."

"What was that?"

"I said, never mind."

"And what else? What after that?"

Clatter of pans, running water. I pulled myself up again, weary, and went into the kitchen. She was standing over the stove, stirring instant mashed potatoes. I couldn't read her back. I held her. "I think we're tearing ourselves apart because the world is coming apart," I said. "1 think you're right," she said. ""Water the plants," I told her, as I went back into the front room, grimly ignoring the radio, the phone, "that's the thing to remember now, remember to water the plants."

It was the fourth night of Cambodia. I was watching the ferns when our brother Lonnie from San Diego came in. "Carol called to find out when you're coming back," I reported. "She says they're working for a school-wide strike on Thursday. The English Department already voted to go out. Farber brought them round, and the paper's agreed to support it."

"AU up and down Telegraph they're talking about Kent State," he said, his face still flushed from walking, intense through his spectacles. "There's little knots of freaks just talking, all along the street. It's true, four were killed, the National Guard shot them down in the parking lots. I can't believe it."

We want to run a training program this summer, for public school teachers in the San Diego area: learn them a little political smarts to protect the Iearning they're learning. Bur Carol can't make the planning meeting, too busy with a crisis in the Woman Studies Program she's organizing in the college there. And she's hard to get hold of now: with the Minutemen at their door, they don't go back to the house much, and are learning to travel armed. Lonnie and I fumble to fix time for another meeting. Nothing will come into focus. He drifts out the door. I say, "Wait." We embrace.

Later Tom calls from over in the next house, to tell me that Reagan has ordered all the state colleges and universities closed, through Sunday at least. Another first for California, the Golden State.

Three years before Cambodia, I visited Kent, Ohio. That was spring 1967, the media were just discovering the Haight and the Hippy. I was on my first round of visiting campuses, just starting to sort things out, to adjust my perspective from Berkeley-provincial to a national scope, and learn what work I could do in our ghetto. For the moment, I was writing a story on what the War was doing to what we then called the Student Movement, and l wanted some unknown dreary large public campus to play off against Antioch and Oberlin. So I chose Kent State, found a contact, and spent a couple of days there.

I mostly remember the flat apathy of the faces I met wandering the campus, these students of lower-class blood slack weary from the mineral-drained hills of upland Ohio, serving time for the upward mobility of the teaching credential. And the buxom girls chattering in the morning Pancake House, as I sat over fourth coffee, road-grimed, hugging my sleeping bag. Flat, that campus, flat. Some months earlier a first hiccup of antiwar protest had turned out a hundred for a lonely march. Now I found all told maybe a dozen committed to keeping active, trying to find a way to move it on. Isolated, embattled, lonely, embittered, taking refuge in an overtight group whose talk was laced with hurtful humor and flashes of longing.

They took me home for the night, the house was old and they had made their warm mark upon its surfaces. They lived in what would become a commune, and then a family. Over late coffee we talked about organizing, about guerrilla theater, about holding together for warmth. Hang on, brothers and sisters, I said ro them, some Spring is coming. And I left them the large Yellow Submarine poster I designed for Mario's birthday -- an anarchist program for a disruptive festival of joy, "a generally loving retaliation against absurd attack." The poster commemorated the 1966 Second Strike at Berkeley -- for us in the West, the first time freaks and politicos joined in public ritual, in song and an elaborate masque. We discussed community programs, wild with the energy of coming together, and broke into spontaneous joy, singing chorus after chorus of "Yellow Submarine" -- imagining all our friends on board, the blue sky, the life-green sea.

Then next October, before I left for my second round of traveling campus work, we put on our feathers at dawn and marched down seven thousand strong into Oakland to block the doors of the Induction Center. After we got the shit clubbed out of two hundred people, we tied up downtown Oakland for the rest of the week, dodging the heat and chanting, "We are the people!" in the intersections.

So long ago. Saturday in Kent they trashed the town in protest, breaking fifty-six windows. I was in Rock Island, Illjnois, with brother Russell from our troupe, talking about the death of a culture and teaching college kids how to begin to play again, to live in their bodies. Sunday in Kent tbey burned down the Army ROTC building. I was home at the house we call Dragon's Eye, sixteen of our family were learning to play a holy Indian gambling game together, a ritual for pooling psychic force, handed down through Stewart Brand of the Pranksters. Today in Kent on tbe fourth of Cambodia two thousand turned out, and they shot four dead in tbe parking lots. 0 let us laugh and canter. 0 I will play the Fool, grant me my mad anger, I still believe that Art will see us through.

October evening falling in 1964, I was standing in Sproul Plaza beside the police car that held Jack Weinberg captive; I was changing in the crucible that formed the Free Speech Movement, the first campus explosion. It was the thirtieth hour since a thousand captured the car and Mario stepped on top to begin the first open public dialogue I had heard in Amerika. Behind Sproul Hall six hundred cops were preparing, around us the Greeks were chanting drunk, "We want blood! "We want blood!" We were sharing our green apples and bread, waiting for them to wade in clubbing, and singing, "We are not afraid," in voices shaking with fear, betrayed into life by our longing for the pure radiations of community which we first there kindled among us, bright as imagination. And I had a heavy flash, and said it to some friend: "Five years from now they'll be killing kids on campuses, all over Amerika." They began with the blacks, with the Orangeburg Three massacred in '68, and they killed the first white brother, James Rector, at People's Park in Berkeley nine months later. And now Kent State: only the first in this Spring when my five years come up.

(Rewriting now on the sixth of Cambodia, plastic underground radio turns real as it tells me how the girl's leg broke as they beat her and threw her off the wall, an hour ago up on campus, and how two thousand National Guardsmen have been ordered into Urbana, Illinois. I've spent ten separate weeks in Urbana, we have family there, Vic centers it, he works in wood and is making a cradle for the baby. Last month I saw him; he was organizing a craft/food/garage cooperative. The week before he had charged the pigs for the first time to help rescue a brother, was still shaken.)

But I had that flash and said that thing, I truly did, and have five years of poems to prove it, canceled stubs on the checking account of my sorrow, a long coming to terms. Sure, I'm a prophet, my name is Michael, I've shared total consciousness and seen the magicians summon the Powers. Prophets are common in Berkeley, and I've met quite a few on the road, mixed with the saints who now walk among us. What else do you expect to appear when our energy comes somewhat truly to focus? It is time to own up to what we are doing. Everyone knows or suspects a snatch of the holy language of Energy, via acid, confrontation or contact. The wavelengths of our common transformations flow strongly through Berkeley: for twelve years now what happens here and across the Bay happens a year or two later in concentric circles spreading out across Amerika. I've lived here all that time. Most leave. If you stay you close off or go mad. Or you stay open and are transmuted, transformed into an active conduit for the common sea of our Energy: lines of its organizing come to flow through you. I think I am learning to feel them in my body. It is frightening, it is always frightening not to have a language in which to wrap the nakedness of your experience. Cold wind of new, hanging on the tip of the rushing wave.

For three years, linked into a growing net of comrades in work, I wandered from Berkeley through our involuntary ghetto. Four hundred days on the road, 150,000 miles: I visited seventy campuses, worked on forty, training and organizing, trying to follow the Tao of transformation in furthering the change that is happening through us. Call me an action sociologist, a specialist in learning and student of change; color me proud to be supported mostly by my own people, freaks and radicals, plus some rip-offs from adult institutions and the media. I hustled to be free to put my energy where I draw my warmth, and luck was kind. And my trip is one among many. Our own and our best are staying with us now, instead of being bought off by the stale rewards of a dying System, and our change accelerates the more.

And I know where it's going, for a little way at least. For Berkeley is truly a barometer. Every college in the country is undergoing an evolution in the culture and politics of its captive transient population; and each evolution is essentially like Berkeley's. I have watched it happening on every kind of campus, from upper-class Catholic girls' schools to working-class junior colleges. Activism begins, diversifies to departmental organizing, anti-draft work and guerrilla theater; the dance of confrontation proceeds in growing ranks; the administration gets slicker but finally blows its cool; dope culture spreads, the girls chuck their bras -- wow, you wouldn't believe the wealth of data. And then beyond the campus the voluntary ghetto forms. Freak community seeks roots and begins to generate communes, families, head-shops and food co-ops, freak media, friendly dog packs and dog shit, links with the farm communes -- there are ten within fifteen miles of Rock Island, micro-sample of Amerika. 0, it is happening everywhere just like in Berkeley, only faster now: long-haired kids on the street, merchants' complaints, heavy dope busts, teachers fired, kids suspended, leash laws, narcs and agents and street sweeps and riot practice for the neighboring precincts and dynamite at the farm-house.

Here now in Berkeley it is the fourth night of Cambodia, Kent State is catching up fast, we shall have to go some to keep ahead. But like the University we have broad strength in our Departments, their lintels display the Tao of Life and Death. The Free Bakery has opened, capacity two thousand loaves a day, put together by a family of forty living mostly on welfare: people drop by to pick up bread or learn how to bake, linger. The city government is trying to get $ 175,000 for two helicopters to maintain a full-time patrol over the city; the City Council has decided not to have its meetings public, because of disruption; we will shoot their birds down, I am sure. A thousand tenants are out on rent strike, now the evictions begin. Governor Reagan is calling for a blood-bath. Gay Liberation flames buoyant in the front lines of demonstrations. Our medics are special targets, speed and smack are spreading like crazy. Six hundred Berkeley families are linked into the Great Food Conspiracy, buying cooperative spinach and cheese. The campus has the third largest police force in the whole county, the leaves are beginning to wilt from the tear gas. The people who hand-deliver a high graphic newsletter to 150 communes in Berkeley and the City, cycling goods and needs and lore and advice, come by and leave us a rap on planting and compost. My kid brother by blood was busted on campus last week, charged with assaulting a police officer with a deadly weapon, i.e. chucking a rock at a cop, $s,ooo bail. He didn't do it, no matter: the Grand Jury's seeking indictments. The leaflet from the Berkeley Labor Gift Plan says, "Together, brothers and sisters, we can build a new community of labor and love." Each time we go into the streets they test some new piece of technology upon us, last week it was cars spewing pepper-fog from their exhausts. The leaflet from the Leopold Family begs the community not to rip off records from the people's own store; they are selling checks imprinted with the burning bank in Santa Barbara. On the radio a brother is reporting from Kent, he says he had to drive forty miles to get out from under the phone blank-out the government has clamped over the area. Berkeley was an exemplary city, you know. She had a progressive form of government and an overtly liberal party in power for years, she dazzled the nation with thoughtful, advanced programs of curricular enrichment and racial integration, active support for the schools was her proudest civic tradition, 0, Berkeley was always noted for how she cared for her children.

Cold wind coming. Sky turning black, the missiles sulk in their cages, the green net of the ocean grows dangerous thin, the terrorism of bombs begins, the Minutemen multiply bunkers, the economy chokes and staggers, the blacks grow yet more desperate, the war is coming home. I figure I'm likely to die in this decade, perhaps in this city I love, down the street beyond the neighborhood garden, in some warm summer twilight when people sit on their porches and the joy of live music drifts out from their windows. That's a cold political judgment, without much to do with what's also true: that since I woke at fifteen I've never been able to imagine past about thirty-five, it's been only a blank in my mind, always the same through the years, down to now, when I'm thirty. Do you mind if I finger my intimate fragments in front of you, awkwardly? I can't fit them together. But what else is a man to do in this mad time, pretend that everything's only at its usual standard of incoherence? For I have also been One with the great two-headed Snake of the Universe, and I have seen us begin to recover our bodies and share our will, seen us learn that realities are collective conspiracies. Now in the families forming and linking we are weaving the blank social canvas for the play of our imagination. I have seen the first sketches of group will, love and art, and a whole life, the first organized forms of human energy liberated one more degree. They transfix me with awe; I was never taught to dream so boldly, I had to learn for myself. I was not alone. For all our failures and unfinished business, what we are pulling together is bright and well begun. If we are let live through this decade and the next we will be strong, strong, our women will be powerful and our men beautiful.

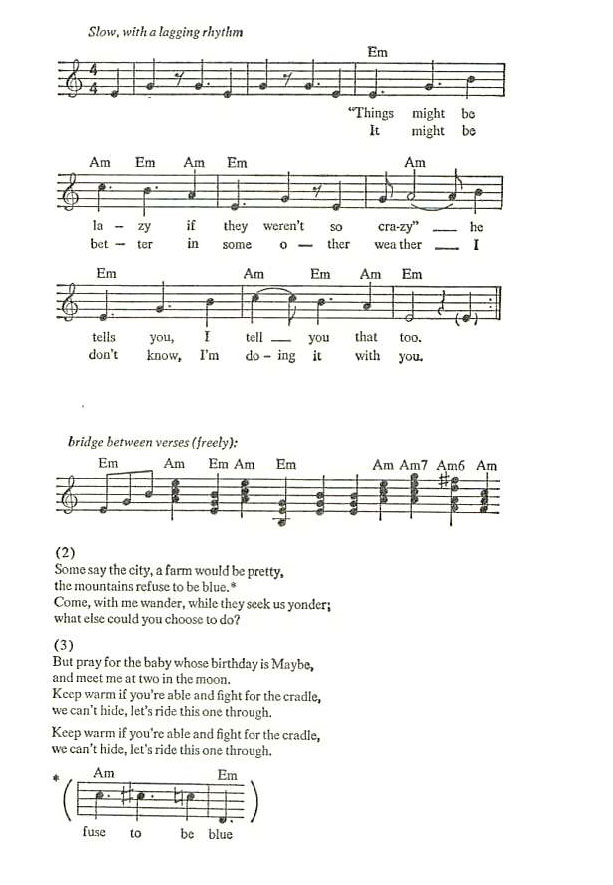

So all of this is running through my mind on the fourth night of Cambodia. I'd just got back the night before from three months of hustling my ass around the country to pile up bread for the baby and the coming recession, in the process cutting through maybe sixty family groups in twenty cities, cross-fertilizing news and goods and paper and trinkets, a bee in the meadow of change. I came back stoned and mellow at how fast and strong it is coming together among us, even within the strain of the War, and bearing the love of a dozen fine women and men for Karen. All day now through the cottage people have been flooding with these atrocity tales, I wallow in the gloomy pleasures of verification. Diagnosis: Fascism, soft form turning hard, terminal cultural cancer. The radio tells me 258 campuses are out on strike, and then sings to me: "Rejoice, rejoice, you have no choice." I take another toke, last of the good stuff: been running too fast to score, and summer's customary drought is almost upon us. The typewriter beckons. Torn between life and death, I calm my chattering schizophrenic, refuse, and turn to the guitar, god damn! the sweet guitar who embraces all of me in her stroking vibrations when I touch her well, 0, how I need to go to the sea!

Music is magical, music is my balm, music suspends me and aligns the frame of my spirit. 0, shit, I wish I could sing to you, I am no longer ashamed, it is time to come out with it all, nothing less will do, the child will be born. I hate these pages, hate these mechanical fingers. Sometimes I pop for a moment above the surface of sanity and grab for the floating flute or guitar, manage to clear the breath of my energy for a time from the choking hurrying flow of vital and desperate information, rapping words healing words data words analysis words magic words maggots and birds on the acid wallpaper of my mind. And I water the plants, the ferns in particular. When I am broken jagged like tonight I think it is because I mostly cannot cry, and that I travel the crystal rapids of melody for this reason too, singing because I cannot weep. When I'm together I see it as a way of keeping in touch with the slower rhythms. Whichever, the ferns are grateful, and they sing to me with their green misty love, and the spiders arch their webs in the corners of the window frames.

And I sing to them back, and to the dog my familiar, and to the pregnant animal Karen crouched unseen in her den -- to them all, but softly to myself -- a song I have made for her from a fragment another singer left in my mind. Karen comes in from the kitchen, plate and bowl of dinner in her hand, sets it down, retreats from the shaken animal in his den. While the rock-cod cools I sing the song again, for the first time loudly.

"Now damn," I think, with bitter satisfaction, "ain't that a song to inspire pity and awe and all! Not bad for a first lullaby, opus 7. I sure would like to spend a long stretch of years writing some songs, be grateful if they just kept coming three or four a year, now that I know they're coming." And I rack the guitar, pick up the plate, and wander into the bedroom to eat with Karen.

In the next room my love is curled weeping on the black leather chair, the dog is anxiously kissing her, careful of her belly, I hold the song of her sobbing. "Ah, little princess," I manage to whisper, "you didn't know what it would cost to be my muse." Through my head spin Cambodia, Babylon, that five-year-old flash by the cop car, growing up during the McCarthy years with the FBI at the door, the times we have been in the street together, our trips, our campus travels. "But there's spin-off, you know," I say, "we're maybe better prepared spiritually for what's coming than most, advantage of foresight and practice, pay of the bruises. We've been making our peace for a while." No ultimate blame: culture changing too fast for its able. But the child will be born, though they tie the mother's legs. "Yes," she says, "but I didn't know it would be this sudden." And then: "But if the gods are stingy with time, at least they've been generous in other ways."

On my lap. I see. Wavering. The plastic plate with pink decal flowers from the Goodwill. Fresh fish filet our cousin family brought us from up the Sonoma coast. Cheese sauce, recently mastered, with chopped green onions. Dehydrated mashed potatoes. In the stoneware bowls Deborah made and laid on us for the anniversary -- before she went down South again to the Army-base coffeeshop she helped start, to watch her successors get six years and then go off to help organize another -- in my dear blood sister's bowls is fresh spinach salad, well-flavored; we are learning to tend our bodies. Anticipation of apple juice in the refrigerator. This is how it is, you see, I am sitting here eating this food, and Bull is watching us very intently while the puppy from next door chews on his dinner, and my feet are up cuddled around the ball of her belly, watermelon-hard in its last weeks. I sing to her, she cooks me food, the dog eats when we do, mostly. She is bearing our child; on the bed under the light and the ferns is the government pamphlet on how to raise a child during the first year; it's not bad.

And she says, ''What do you think of Lorca?" "I think I can dig it, for a boy," I say, slowly, "I been thinking about it, and I can." "I'm glad," she says softly, the blush of shy triumphant pleasure crowning round her eyes, ''your mother and I were having lunch, and we started to think of names of Spanish poets. 'Garcia Rossman,' she said, 'no, that's impossible.' 'Federico .. .' I said. And then we just looked at each other, and we knew. And it has a nice sound."

I sink into the thought and mirror of her love, reach for the resonances, roots in the soil, and start to cry. Is it for the first time or the tenth, on this fourth night of Cambodia? Lorca was my first song teacher, the man who opened the keys of Metaphor to me: for ten years I relived his poems into my American language. "I have lost myself many times in the sea," he sang, "with my ear full of freshly cut flowers, with my tongue full of love and of agony. Many times I have lost myself in the sea, as I lose myself in the heart of certain children. . . ." Hold on, dear heart, jagged at this four A.M., now is not the time to tear. From Federico's arms I passed through those of grandfather Neruda, and then into Vallejo's volcano, which finished for me what acid began and gave me open form to integrate my fragments.

But Lorca began me, long before I learned how death found him in a Fascist trench, how he went to sleep forever in the autumn night of the gypsies, beyond the lemon moon. Mercurial brightest spirit of the second Golden Age of his tongue's power, murdered in Granada by Franco's highwaymen, in the first summer of the Civil War. All the poets, all, all the singers were on one side in that great division, perhaps as never before since old Athens. And the schools and the hospitals of the brief flowering of Republican Spain went down under German planes and Italian artillery, the dogs of Church and Greed. And all the poets perished or fled.

Torn, my father watched the Fascists rehearse, with their scientific grace; stayed to organize at home with his trade of words and a red perspective. I was born six months after Madrid fell, while he was editing the Mine, Mill and Smelter Workers' union paper in Denver. Pablo Neruda was in exile from the Fascists in Chile. Cesar Vallejo was dead of hunger and heartbreak for Spain. Lorca's grave was never found, in a hundred lands and Franco's jails the poets of his race who survived sang him their tenderest elegies. Lincoln Steffens began a new family and life at sixty, his Autobiography instructed my father. When he died the last lines in his typewriter read, "the Spanish Civil War is the opening battle in mankind's struggle against Fascism." Steffen's son Peter taught my sister Deborah before she went South; I have touched his children. Even the high school babysitters I hitched home from the airport with know what's coming down.

A week before Cambodia I was at a conference in Boston, thrown by some church folk and book people, on "the religious dimension of the Movement." Indeed. It was quite a happening, believe me: a bunch of us freaks from the families got together behind some mellow mescaline and opened up some free space, some Chaos. And then someone asked about Ritual, and little incredible Raymond Mungo opens up in a musing country style, speaking the sainted baby babble.

Well, we get up in the morning, he says, and we look at the light and we eat, we eat together. And we go to sleep when it gets dark, sometimes alone and sometimes together, for there is no light. But sometimes at night we watch the moon. During the day we plant. We chop wood. We use the wood for fire. We eat when the sun goes down. From April to October there is very much food. We have to find ways to give it away. We have to, there is very much. There is the summer solstice, and then there is the autumn solstice, and so on. In spring the solstice was very cold, very cold. We chopped some wood and put it in a box. I made a mantra: Equinox / sticks in box / soon it will be warm / big dog. And a big dog came, and it grew warm. And sometimes we go out when there is no moon, and run around in the grass. And then we come back to the houses we build. Last week one of our houses burned down, it was very warm. We lost four brothers and sisters. I think we're going to learn to build better chimneys.

0, I met a little saint in Boston, he organizes energy, used to be a founding Czar of Liberation News Service, then he figured out the cities were dying, now in his Vermont town of eight hundred over a quarter live in communes, and he studies the government pamphlet to learn to build better chimneys. We're met on the fifteenth floor, overlooking the river of death called the Charles, the plastic pastries and draperies are poisoning our bodies, our minds, we've come to talk about rituals for living with fire. Mitch Goodman loves us and he's frantic with terror, sees the black sky looming, MIRV's lurking, etc. etc., he's positively yelling at Raymond, half his age and weight, scarecrow child in oversized coveralls: But what about Fascism!? And somehow we can't quite get it through to him there that Raymond is not simply talking about farms, pigs, dinner, etc. but about the house burning down and learning to make better chimneys and going on in season, and about Lorca and Vallejo and my brother and my sister and two of each dead in Kent and my lover lazy with child, whose belly my baboon feet grip as if I stood on the round of the world, spinning through all time.

I was translating a poem of Lorca's when I got the call that my grandfather was suddenly dead. It follows a brief skit for puppet theater, in which the gypsy whose name is Anything is captured on the bridge of all the rivers while building a tower of candlelight. He is brought before the Lieutenant Colonel of the Spanish Civil Guard to be interrogated.

He, Aaron, my mother's father, was a Bolshevik; he organized a strike in the machine-shop, was jailed, loved his tutor, she died of consumption, he fled here in 1906 to dodge the interrogations of the Czar, clerked and warehoused to send Mom through college; he wanted her to learn. I have his blue eyes. He taught me to carve, cried with memory when I told him in '60 during that Spring of Chessman and HUAC how they beat us and hosed us down the steps of City Hall in San Francisco. "That was how it started, you know . . ." he said. And three years later the phone call came and was, and I put down the receiver and thought for a moment, and said somewhere inwardly and quite distinctly, I will file this for future reference, I will weep for you some day, grandfather. And I turned back to finish reworking the poem, for there was nothing to do but go on; I knew it would take years to comprehend that grief.

Sitting in my rocker, plate on my lap, our eyes intertwining and my feet on the future, the ferns turn to oleander and the cottage to a patio, and the song of the beaten gypsy rises up in the well of his absence.

Twenty-four slaps,

twenty-five slaps,

then at night my mother

will wrap me in silver paper.Civil Guard of the roads,

give me a sip of water.

Water with fishes and boats.

Water, water, water.Aii, boss of the Guard,

standing upstairs in your parlor!

There'll be no silk handkerchieves

to clean my face!

And the tears rip through me grandfather deep and out everything open and echo in hers, and we touch and cling and are shaken. And the dog our first child and familiar pushes up anxious between us and offers her his nose and me his nads, which we take to complete the circle of energy, love, and time around the child to be born in Cambodia. "Yes," I say, "Lorca, if it's a boy." "Maybe even a girl," she says, "it has a nice sound." "Maybe a girl," I say, "yes," and she says I'm glad with her eyes.

And the radio sings, "Rejoice, rejoice, you have no choice," and the acid magic of those moments, of that state we once called existential, goes on and on forever, and I go off to set down the brief notes of these thoughts, like the rib-thin eaten skeleton of the dinner fish, to flesh back out later. And then we take off for the City, to try to be with our people, our theater troupe in rehearsal coming suddenly real. For it is clearly a time for coming together with those we are dear with, and we must take care that the Wedding go on within the War.

May 1970