IV. Open Space

Learning as Death and Birth

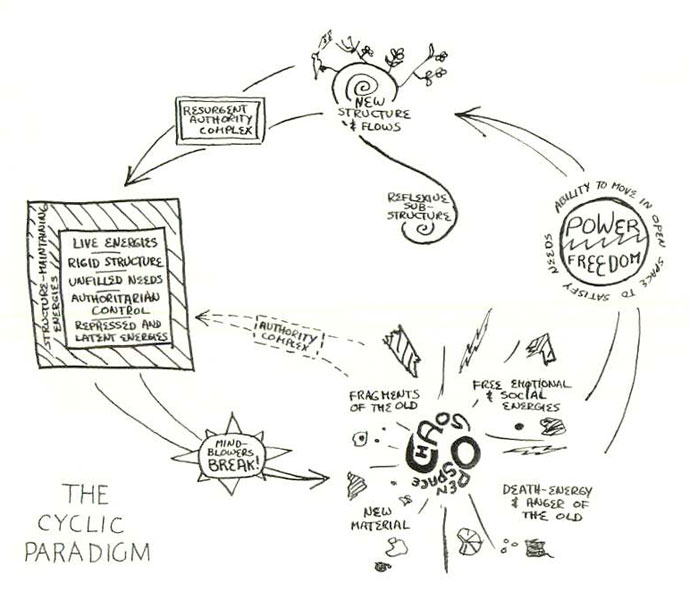

Begin with a simple cyclic model to describe the act of learning or of social change.

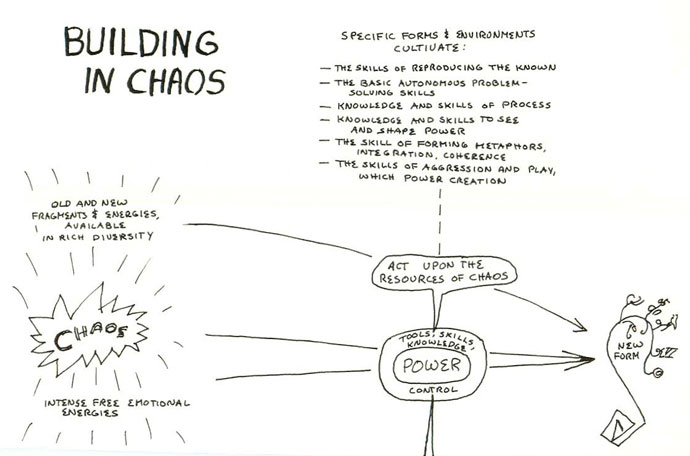

Human energies, bound and flowing, form a stable system. Some are involved in maintaining the structure; some are expressed though it, with various degrees of health; and some are repressed or latent, connected with unmet needs. The structure breaks. An open space without coherent structure results: a Chaos. It contains not only the energies expressed or repressed by the structure, but those formerly bound in maintaining the structure's coherence, and the scattered fragments of the structure itself. In this live open space, tools, skills, and knowledge under some form of control -- freeing or authoritarian -- act upon and with the energies and fragments. Out of Chaos, a new coherence emerges, a new structure. Energies flow and hang until change again becomes necessary, and the process repeats.

From this perspective, significant learning or change in human systems is always explicitly revolutionary: it involves the death of one order and the creation of another. The rhetoric of this description is social and dramatic, at odds with our cultural mythologies about learning. In the real physical world, of course, change has proven to be quantized and discontinuous. But our social sciences lag behind our natural ones.

Whether the change be the elimination of racism, the learning of a mathematical theorem, or the recognition of love, what is involved is always the disruption of an organic human system, its death as an integral entity; and a birth. After learning to conjugate a Spanish verb or express a sigh, the new human system does not differ much from the old. But it is new, and its birth may become easier and more appropriate when understood as revolutionary. (1)

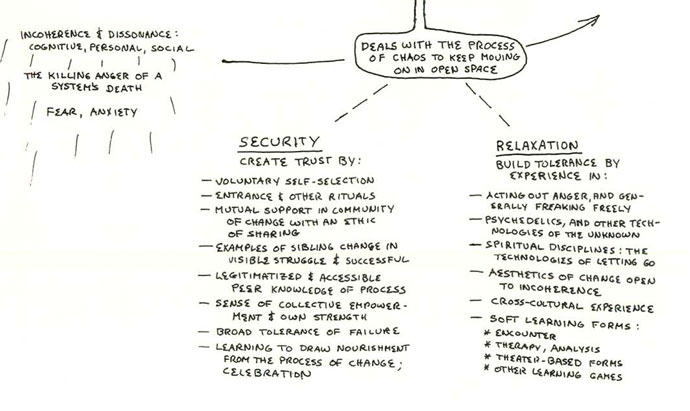

If learning is revolution, the goal of our new education is not a degree or a state, but a process: a healthy process of change and its attendant skills, in response to our needs and desires. Our learning to create this process seems to have three components: learning to break free from old and crippling frameworks of control: learning to think about the process of change; and learning to handle and build in the freedom we create and grow in.

Given this cyclic model, the key questions of learning theory become these: How is open space created, recognized, and maintained? What happens within it, and what is it good for? What skills and what forms of authority and control are necessary to survive and to build with health in Chaos? How are they developed? How can we construct human systems that will die gracefully when their time comes, or at least leave their people empowered to build in response to real needs?

Some first answers to these questions appear when we examine my generation's experience with free learning in open space. (2) For we are involved in a many-leveled system of alternative education, which transforms us as we invent it; and by considering its examples we can accumulate a more detailed model of our working knowledge of the process of change.

The FSM and the Open Circle Model

The Cop-Car Episode

On October 2, 1964, a police car drove onto the main plaza of the Berkeley campus of the University of California to arrest a young man at a civil rights table. A thousand students entrapped it with its hostage, and the Free Speech Movement began in high gear. A microphone was placed on top of the car. Sock-footed, Mario Savio stepped up to speak. He was followed by two hundred others. From that unprecedented podium, they spoke for thirty hours, creating the first true public dialogue I had heard in America.

The open space was not only that created by the neutralization of campus and legal authority. It was an internal open space of live energy gathered without expectations to limit its expression. No one had ever captured a cop-car before, nor spoken from its top within such an immediate, deep, and ongoing crisis: no one knew what form of speech was appropriate. Hence a diverse multitude of viewpoints -- on history, politics, poetry, morality, law, tactics, and our feelings appeared from a richly various population. None dominated or subordinated the others -- unlike a normal political rally -- which is to say that no central Authority was re-created. This permitted a deep commonality of feeling, perception, and intent to emerge.

It is hard now to remember the fragmented alienation that was the endemic state of pre-FSM Berkeley. In the open space around that car was born a long-latent group consciousness, which since has broken and reformed many times, growing slowly stronger and broader, into Community. At that moment it was sufficiently intense and coherent that, for the first recent time within white America, a group of her young were willing to face beating and arrest by 600 cops to defend what was theirs. In the pure, energy-filled Chaos of that conversation a shared understanding was born also. The politics, analysis, and strategy of the FSM were realized full-blown in those early hours; and the next three months of this first major campus movement were devoted to working them out in practice.

The Movement's Structure and Process

This working-out was accomplished in a different sort of open space. The FSM had a visible political structure: campus groups sent representatives to a large executive assembly responsible for policy-making, which elected a small steering committee to make immediate tactical decisions. But neither body had any significant control over the movement's members and their voluntary actions. Their main functions were in fact to handle information: to coordinate its flow within the movement and across the interfaces between the FSM and other campus power-groups, and to represent the FSM formally to the outside world. Power of course resides in the control of information, but at worst such power is only indirectly punitive. In this case it was used to enable the FSM's members, by making information-flow within the movement as free and comprehensive as possible (thus decentralizing power).

A distinctive style of organizing social energies resulted, one familiar to crisis politics. As a need became visible, a group of volunteers organized spontaneously to learn to fill it. Quickly some thirty autonomous groups involving over a thousand people appeared, to fill a spectrum of functions ranging from legal support to entertainment, from research to publicity. In general the two central committees were powerless to define, order, or direct their work; they could only facilitate it when possible, and by spreading its information help to spread its example and style.

Later accounts tried to explain the FSM's power and success by picturing it as efficient and highly organized, run by a core of highly skilled technicians, like some functional American bureaucracy. In fact, it was nothing of the sort: groups would form and be working for days before the steering committee even learned of them. Skills were mostly developed in situ, in a process of free learning, from fragments of past skills and training usually meant for other purposes. I had never before seen my peers able to come together on a mass scale and generate new work in response to their needs. Here many of America's elite and frustrated youth felt for the first time that they created coherent, satisfying, and productive work that used their human capacities. The space they moved in was both open and rich, in senses they had not encountered before.

The Universal Sit-In

The FSM climaxed in the first mass disruptive campus sit-in. A thousand students marched into the administration building "to bring the machine to a grinding halt." They expected arrest and police violence as well as suspension or expulsion from school.

In the freed space of that building, during the fifteen hours before the cops came, the nation’s first free university conducted its first classes atop civil-defense disaster drums stored in the basement. Movies were shown on the walls. A Chanukah service was held, followed by traditional folk dancing. Singers and instrumentalists performed in the stairwells. They were barred from the study hall to which the top floor had been converted, and avoided the improvised infirmary and kitchen. Pot was smoked in the corners, and several co-eds had their first full sexual experiences on the roof, where walkie-talkies were broadcasting news to the outside. The steering committee made political decisions in the women's john and organized in the corridors.

To an open space -- here physical rather than political or conversational, and of course always psychological -- the students brought their entire selves and concerns, true to the deep and multileveled nature of the conflict. The result was typical of what flowers in open space. Masquerading as a sit-in, an entire society-in-miniature was created in the liberated territory of Sproul Hall, using all the resources available.

Confrontation Politics and Personal Growth

One aspect of the FSM illuminates the question of liberation and growth, and the connection between their social and personal levels. In the six months following the sit-in, literally everyone I knew who had been deeply involved with the movement accomplished some major and long-delayed change in their personal lives. Examples were various: they left school, town, or their mates; some decided to finish their Ph.D.’s, take up painting, stop smoking, or get married. For all, the changes were intimate and deeply therapeutic.

Thus interior psychological space was opened by participation in a highly successful mass movement. Two factors seem clearly involved. First and simply: a sense of public, collective empowerment carries over into the private domain. Social behavior that shatters expectations of what is possible creates psychic space, in the form of a larger, partially-opened universe of personal possibility. (Conversely, individual learning of all sorts is inhibited in a stifled society.)

The second factor has to do with why people were in fact able to move in their open spaces, and is more complex. In the FSM, the anger of America's white young was directed for the first time against their parent, liberal institutions. All observers agree that a long-gathered and deep anger and frustration -- with the institution's processes and effects on the students' lives, and with their own inabilities to function -- provided much of the energy that built and ran through the movement.

These gathered emotions were catalyzed into available energy during the charged hours around the cop-car, while students discussed the administration's inept atrocities and waited for the cops to recapture the car. For most, it was their first serious demonstration. Each had to deal directly with his own live anger and fear -- the immediate tip of a massive iceberg -- and manage some temporary resolution. Most chose to stay, to resist dispersement nonviolently and continue the struggle afterward, and to face and endure the uncertain consequences of their choice.

The movement's later development can be viewed as the acting-out of anger in a social theater: the articulation and expression of collective repressed emotion. The main target was the administration, which continued to provoke conflict during this time. In widely varied symbolic theater, the students dethroned the coercive parental authority described above as the Authority Complex. Harsh emotions became tools to break, rather than reinforce, control. In the open space thus created, and in response to their other feelings and needs, there flowered a rich and various community and culture, and a multitude of individual changes.

Observers of campus conflict are familiar with the enormous amounts of energy liberated in the participants, with the striking efficiency of its translation into productive social and personal work, and with the heavy charges of anger and fear that must constantly be dealt with on many levels. It seems that to engage directly with these emotions is deeply therapeutic and freeing in a nonspecific way.

I believe that this connection between personal growth and the experience of being able to express anger holds true on the largest social scale, though modified by other factors, and is critical in explaining the connection between the recent political movements among the blacks and the white young and the broad movements of cultural change that are spreading in their wake.

The Open-Circle Process

Let me turn to a model of a learning environment that exhibits more directly the cyclic paradigm of learning sketched above. Its main features were visible in the cop-car episode; I have observed it in many other contexts and have created some of these deliberately. As a mass-learning form, it can be used as a tool with a high probability of successful operation under the right conditions. These include the presence, among a group of people, of a sufficient critical mass of emotional energy -- long stored up, or attached to some recent event -- and the need to create a public consciousness, not at alI monolithic, which individual consciousness can relate to and be defined against.

Several hundred people are seated in a circle -- the geometry is psychologically significant. They include a small core-group that organizes the form's energies by catalyzing and maintaining open space. The process begins with the breaking-open of space, through exhortation or ceremony, or a piece of angry or joyful theater, like the ritual murder of interrupting a planned speaker. The event must combine naked emotion with heavy and appropriate cognitive content; the dissonance between these is crucial to releasing energy. The aim is to provide a freeing example, to break open the expectations of what can happen in the circle, to provide an authority that does not limit or enforce appropriate behavior but gives permission to express what is there.

The core-group keeps the process open by preventing the redevelopment of the Authority Complex in any of its forms -- such as a faculty member speaking at length or in continual response to questions from students; prolonged two-person debate; cooperative effort by a small sub-group of sophisticates to keep the conversation focused on a narrow ideological track; and so on.

The core-group deals with the steady resurgence of the Authority Complex by isolating the individuals responsible (if any) and effectively removing them from the conversation: by making new behavior to break the expectations that re-form even without provocation; and by speaking directly to the larger group about the health of its process. The core organizers must deal also with the Authority Complex latent in their own presence, especially while the impact of the opening event lingers. (For example, the larger group must not feel that it is necessary to put on a show or stand naked in order to speak in the circle.) The core-group defines space with its energy, then draws back to leave the space open. When core members speak with the authority of organizers and tenders of the discussion. they speak only of its process. This authority must not be used to lend false weight to their personal speech as members of the whole. If this distinction is impossible to maintain. as is often the case in large groups, they are silent personally.

On one occasion, two of us began such a process among students at an educational-reform community meeting. All our past expectations and conditioning urged us to hang on to control after we first spoke. My companion kept calling on people and asking them to focus their discussion; I sat on the floor cross-legged, rocking violently, acting out with my body my frustration at knowing what everyone should, of course, agree upon. Finally I controlled him: sent him to shush musicians at the back so people could hear, and do other control-things to facilitate the meeting. Our drives to control were thus neutralized in the conversation, which went on for hours with high tension and freedom.

The pattern of a successful open-circle process is generally this: For, say, half an hour after the opening, speakers cope with their reactions to that event. These are always quite mixed and include much hostility (which usually accompanies the breaking of expectations). Then people's less-transient concerns take over. The conversation becomes various, not uniform. It is not debate, being poor in counterargument, nor continuous logical development of a topic -- the style of authority implicit within such forms of conversation is not flexible enough. Rather, the key mode of an open process is testament. Freed not so much from direct constraint as from the subtler tyranny of limited example and expectation, people improvise to fill space with whatever they have to express and feel is appropriate. They speak as the public fragments of a divided consciousness. When enough fragments have been presented so that the consciousness becomes clear enough for individual and group needs, (3) the process is satisfied, and typically breaks up without a climax or a formal closing ritual. When the process is working well, most of those who speak are not accustomed to performing in the public of their peers, and the emotional quavering in their voices as they present their real concerns is the surest index that open space has in fact been created.

As with all open processes, the quickest way to close this one is by creating a climate of fear. Most open circles fail when their speakers turn from testifying to arguing against what others have said -- reasserting by their stance of Critic the presence of the Authority Complex they have internalized.

Examples of Social and Cultural Growth in Open Space

Some understanding of how growth occurs in open space comes from examining five major social and cultural institutions now being developed by the white young.

Underground Radio

The prototype "underground" radio station was San Francisco's KMPX, which early in 1967 began broadcasting an after-midnight hard-rock-and-rap program once a week to the enormous latent audience of hip young in the area. KMPX was then an obscure, struggling FM station, its airspace weakly held by a polyglot of ethnic/religious programs. Given the response to the new programming, the station was open to displacing the old segment-by-segment. Within a year, KMPX radiated New Culture twenty-four hours a day to an audience exceeded only by one local AM station, and changed the listening habits of a growing community.

Since KMPX was the first of its kind, there were few past expectations to guide and limit the conversation of its growth. Programming began by freely exploring the rich and changing music we called rock, and then expanded to include Bach, Ravi Shankar, jazz, music concrete, and old radio serials like "The Lone Ranger." Drop-in interviews with musicians and others of interest to the audience began happening unannounced. Sunday afternoons developed into a forum on matters of community importance, like abortion, the Great Pot Test Case, and the Vietnam War. During a local newspaper strike, KMPX broadcast favorite columnists and a daily news summary compiled by the left magazine Ramparts; a sister station went on to develop a new and wildly inventive form of dramatized news presentation. KMPX began to generate dances and demonstrations almost by itself. Its announcers were casual about mistakes and used frank language. They announced the arrival of pot shipments, reported lost dogs, and warned listeners about batches of poisoned LSD for sale.

In an open space, a many-faced institution was growing in response to the unmet needs of an emerging community, generating new ideas and examples of what a radio station might become. The speed and flexibility of its growth were directly due to the high degree and quality of feedback between KMPX and its audience. The announcers and engineers belonged to the community and responded to its constant phone calls, often putting them on the air. The station was even physically open to its listeners, who crowded in bearing food and their desires. (4)

The open space could not be maintained. The station's success made it the focus of powerful commercial and social influence from the larger society. Within a year, control of the broadcasts passed from the programmers to the station's managers and owners, and to undiscriminated advertisers. None belonged to the community; all represented outside social and economic interests. In a classic sequence, the Authority Complex re-entered and pruned KMPX's brief various garden back to acceptable limits. The station's staff struck to regain control, were unsuccessful, and left. KMPX's programming went downhill to a safe plastic hip style. The original staff was powerless to better this when hired to revamp a station owned by a major media-chain, for its style of control proved inimical to freedom.

By 1970, there were three hundred "underground" stations. Few had enjoyed even KMPX's brief flowering, and almost none had developed significantly beyond that model. The lesson is general: only collective control by the community involved in and affected by an institution can keep its space open. (5)

Rock Music

"When the mode of the music changes," said Plato, "the walls of the City shake."

The art medium now called "rock music" deserves study as an open social form. Though rock is blues-based, its evolution has been so rapid and decentralized that -- in contrast to tradition-rooted forms like jazz and classical music -- an Authority Complex operates relatively weakly within it, and its limits are radically open. The form's technology is one factor in this -- since records and tapes are cheap, plentiful, and ephemeral, their influence is as unconstraining as their production is rapid. Also. rock is generated from a remarkably decentralized base of small, changing groups with wide-ranging cultural inputs, who are rather responsive to local community audiences. The freeing style of authority inherent in this generative form works to keep the medium open and preserve its vitality.

In this open domain, the young are inventing music anew, with a freed sense of what is appropriate to the task. The measure of a form's freedom is the diversity of behavior it contains and develops from what is available. Rock now embraces and integrates musical styles and elements drawn from every American subculture, and from most major musical cultures known to the rest of the world and to history. Its instruments range from violins to computers, from tin pans to theremins. Its content -- as the Birch Society has long recognized -- is a many-leveled message about freedom and the destruction of the old style of authority, which is mirrored in the structure and process of the medium that bears it.

But counter-forces work to close the medium. By 1969, they were already beginning to damp its live diversity. Though the music was created from a decentralized musician base, it was produced and distributed through the centralizing apparatus of the music industry, which operates in hierarchical power-modes within an economic reward/punishment scheme, for the sake of preserving and extending its order. And though music is of all expressions the one in which the intrinsic authority of example should carry most clearly, within the Form of rock the force of an overriding Authority Complex has biased evolution and has restricted and standardized the language.

Here we can study in some detail authoritarian closure as it occurs in a communications medium. As a mediating valve in the cycle of energy between musician and listener, the industry regulated the information it carried. The principle of regulation was neither free dissemination of all (musical) viewpoints, as in an open-circle process, nor the focused dissemination of a community consciously putting a medium to its own constructive use. Instead, the industry chose music to push on the basis of its potential marketability in profit competition (and cultural "safeness"), and promoted musicians on the basis of their integrability into industrial production. A minute elite of decision-makers reinforced these choices with sales propaganda which tapped all the conditioning of their audience to re-create the hierarchies of Star and Superstar and convince people that what they got was what they needed.

Through this authoritarian valve, the rich output of people's first explorations of the open space of a new Form was restricted. Hardly was the Haight unveiled in '67 before the record companies were at work to define and market a pablumized San Francisco Sound. The Top Forty DJ's, their monopoly of most city audiences still unbroken, played it to death as an “in” thing. In thousands of garages across Amerika, kids hungry to make it as a group grabbed at the Sound, seeking something sure to get it on at the high-school dance, something the local promoters would find likely, or just one cut to send to RCA. Through a multitude of such cycles, rock music has grown stale. As of 1971, this Form was back under familiar control.

Rock Dances

Rock music has an open and eclectic aesthetic, which characterizes the other art forms -- painting, clothing, poetry, graffiti -- the growing edge of the young culture, and which is foreign to the parent culture. Call it the Santa Claus Aesthetic, for one never knows what the medium wearing it may bring. This aesthetic is a phenomenon of first growth within freeing forms, fed by open access to treasuries of raw material. Yet it may not be ephemeral. For the Santa Claus Aesthetic is surely also a function of the emerging nature of those who invent and delight in its gifts: and perhaps, in this age when we resurrect and ransack the cultures of the world and the past and human consciousness transforms itself by miraculous technologies, it may presage a stable cultural style new to human history.

Such dreams came naturally in the heady atmosphere of the first rock-dances, held in the now-legendary Fillmore Auditorium and elsewhere in San Francisco. "Rock dances" is a thin misnomer for these first successful experiments in mass total-environmental theater. The battery of media employed has become familiar: films, liquid light projections, stroboscopic and "black" lights; incense and foods and feelables; live music and tapes. Their total and many-leveled impact overwhelms psychic barriers. To attend simultaneously through several senses to intense semi-related messages creates an internal dissonance that expands and opens inner space. Technicians of the mixed-media form were immediately familiar with the behavioral consequences of what they called "sensory overload."

The great halls held open space: physical, psychological, cultural, historical. Live energies of longing and contact refracted through a myriad of cross-cultural interfaces to open space further, as Hell's Angels, hippies, media-men, activists, socialites, teeny-boppers. blacks, and sorority girls came together in fantastical costume. In that space people sang, danced, rapped, took pictures, played instruments, voyeured, seduced, served Kool-Aid, painted faces and floors, spun in rings, stood drowned in light, freaked on acid, wept in corners, played balloon-ball, took notes and chanted, spun wildly through the crowd crowned with ivy or in the raw. There were no necessary roles, no established norms of clothing, conduct, or motion. Beyond their irreducible interior imprisonments -- often dramatically lessened -- the participants were free to define themselves and "do their own thing," even though that phrase was not yet current. The halls became a rich, compact arena for the free, improvisational theater which the young are developing now in the streets, classrooms, and supermarkets. (6)

In America and the West, the white young had always learned dances created by others, sometimes varying them slightly in learning. In this process -- caricatured by the white feet and black feet, 1-2, 1-2, of our childhood comic books and adolescent social nightmares -- the structure and operation of the Authority Complex are elegantly displayed. But in the open space of the Fillmore Auditorium, many were freed to learn a new style of learning how to dance. In a whirl of motions -- polka and cha-cha-cha, ballet spins and gymnastic stretching exercises, mambo and bunny hop, twist and camel, waltz and intercourse, kaleidoscope modern dance -- from a treasury of fragments and their own natural gestures they learned to synthesize dances whose names were only their own, relegating imitation to its proper place in the process of free learning.

The closed universes of personal possibility were broken open by the force of mutual example. In a climate that tolerated any collection of motions, guided by their own senses of coherence, individuals created and expressed their own dances. They were limited primarily by their physical capacities; by their abilities to grasp and combine disparate elements into coherent expression, and to tolerate the cognitive and other dissonances centrally involved in this process; by their senses of trust and fear; and by what they had in their selves to express. The particular importance of dealing with fear in this process of learning will be clear to most who remember learning to dance (even in a crippled way), or who strive for emotional openness.

Mixed media are not enough: the open space was not maintained, within the halls or for persons. The halls settled into successful commercial operation, in the familiar centralized forms of the profit economy. In ways direct and subtle, and in the style of the Authority Complex, this re-enforced old limits on behavior and expectations. This process was even acted out physically, while the capacity overcrowds of greed were compressed into a uniform mass on floors that had no space for dancing, and life-theater turned into passive concert.

This process of closure took about a year. The mass media played a considerable part, by shifting the nature of the audience and its expectations. But I do not think they hastened closure, despite the way we cursed them for cheapening this too. For, though closure processes are various, their common period seems to be some nine to eighteen months, (7) in any new form or institution that does not contain a sub-component that functions explicitly to keep the form open. The process of closure begins when dominant power relationships, in social or psychic space, start to be seriously challenged.

The Fillmore moved to Fillmore West, which might better be called Fillmore Lost. But its prototypical classroom for personal and freely developed dance and theater continues to be re-created at be-ins and happenings -- especially at those felt to be of historical and cultural importance. This Event consciousness is instrumental in creating open space. It is one version of the Hawthorn Effect (8) -- a general term for the way people's behavior changes when it takes on the important aspect of being an object of deliberate study. (The Effect is radically different when study is evaluation within a punitive framework.)

Two other factors involved in the successful creation of this learning form deserve mention. Typically, as in crisis polities, there are many objects, groups, actions, and individuals that provoke and invite participation and active response. From one perspective, this means that the drive and instinct of play are strongly excited; from another, that as a functional form such a process of energies is rich in feedback loops. Also, these events are often free, both in the simple economic sense, which is psychologically important, and in the deeper sense of an ethical mood prevailing -- one that licenses giving out and sharing without requiring return, and is often catalyzed by the example of the musicians.

Free Youth Ghettos

History has known other youth ghettos, less extensive and deliberate than those being created throughout America. Never have tbey contained "youth" largely in their twenties, nor served as the principal cradle for what Kenneth Keniston (9) speculates to be a second, para-adolescent developmental stage unique to post-industrial society and thus to human culture. Robert Lifton has given us the term "protean man" for the selves that may be the full products of this stage: selves capable of wide and continual transformation and application, bearing with them their conjugate society, which also may be called protean. What environments of learning and change will produce them, and how? This is perhaps the key analytical and political question of our age; surely radical social reconstruction depends upon it. One way to begin to poke for answers is to try to identify and understand the real leaming processes that have so far been at work among the young who provoke these speculations.

America's free youth ghettos still largely coincide with her college campuses, where they first developed in an incomplete form. Now, in a fuller form, they are growing in every major city. Their prototype appeared in San Francisco's Haight-Ashbury district.

Over a few years, perhaps 10,000 of America's most freed youth occupied the open urban space of a declining neighborhood, seeking with varying deliberateness a place to build a local society that would extend and embrace their individual changes. A tenuous ghetto grew denser. The Haight came to collective consciousness of itself as a distinctive place roughly at the end of 1965, aided by a successful neighborhood political battle to avert the carnage of redevelopment for a freeway. This consciousness was marked and defined by the development of a spectrum of small formal and informal groups -- political, social, cultural, economic -- whose functions were to clarify the nature of the society emerging there, to guide and express its growth, and to begin to develop institutions appropriate to its needs and nature. (See chapter X)

The Haight flowered in peaceful space for roughly a year. Then the mass media discovered it and created the Hippy, and it was swamped by an instant media deluge whose only precedent was the destruction of San Francisco's North Beach colony a decade earlier. The hospitality, trust, and resources of a young society were overwhelmed and its further growth was agonized and distorted. While Scott MacKenzie sang, "If you come to San Francisco, wear a flower in your hair;" the speedy economies of tourism and Mafia amphetamine pumped strange elements into the open arterials that nourished the Haight. When the hungry young arrived in force, they found a social sewer.

But there was another, ephemeral Haight never captured by the media, whose development, nature, and destruction have been described only in fragments already outdated. That story is equally about the growth of freedom in America's young, as their lives sketch a new society that feeds cruel hopes of its possible survival, and is too complex to go into here. Still, the original Haight presents some important parallels to the "rock dance" model of a learning environment.

First: The individual consciousness of its members was opened not by multimedia sensory bombardment, but by an analogous process in more general media. The catalogue of input is hopelessly long. Television brought the first indelible images of black liberation. The Bomb spoke in their nightmares, while they listened to a new music on transistor radios, read paperback science-fiction, dreamed of touching the moon. They were exposed to all the explosive potential liberations of a sudden qualitative change in man's social and industrial technologies, and to the deaths that these equally threatened. Raised among the gathering contradictions of a liberal corporate capitalist state unable to cope with its problems or maintain its authorities, the inner barriers of their perceptions were corroded by casual lay psychoanalysis and psychedelic drugs. The media were new and penetrating and bore intense, discordant, incoherent energies and images of life and death. The young came to the dance hall called Haight with their minds blown.

Second: The social norms of the Haight were those of its dancers at the Fillmore writ more broadly. They defined a context whose participants were somewhat freed to explore the dance of their selves as they had that of their bodies. There was no effective collective concept of deviant behavior. The boundaries of permissible and possible behavior became drastically enlarged under the multiple thrust of radical examples.

The media phrase "do your own thing" is a weakened version of the Haight's acid motto, "freak freely"; and members of the broader community now becoming self-conscious in America most commonly refer to themselves as “freaks." To freak freely is to let out fully and live in the energies and natures that have been repressed by our society through a process most usefully described as "niggerization": a process in the style of the Authority Complex, which inhibits the development of individual and cultural identity. The concrete experience of life among people who gladly think of themselves as freaks, as niggers learning the beauty of their black and other selves, is a carnival dream. For in a climate with almost no operative concept of deviance, bewildering in its variety of cultural input and individual example, personal change becomes richly possible.

Third: Of course, collective values and aesthetics were also revealed and developed in the space opened by the drastic diminution of that internalized Authority Complex that governs public and private behavior. The emotions of varied and explosive personal liberations overlapped and reinforced one another. They encouraged exposure, sharing, tolerance, mutual involvement and support. Norms and expectations of behavior developed, whose authority was freeing rather than constraining. (Their tangible symbol was the Haight's most typical social ritual, the offering of a joint of grass to the friend or stranger entering through the open door.)

Within the space they opened, much that was ugly occurred -- though more that was beautiful -- in terms of specific aesthetics that people shared. Indeed, the public presence of ugliness and failure seems to be one essential feature of the operation of an open form. (11) For such a form to continue successfully, its beauties must overbalance its uglinesses in a way that nourishes a commitment to an overarching aesthetic of freedom within which individual aesthetics can be pursued: and it must develop ways to deal with its failures. Making failure a visible and acceptable element of process is a necessary beginning. In this as in other ways, the parallels to personal therapy should be clear.

The imprint of a collective aesthetic of freedom is apparent in both the intent and the design of the institutions that began to evolve in the Haight to service basic human needs. Successful experiments in creating and distributing on a mass scale free culture, free food, free housing and clothing, free mass communications, and free medical and legal services began and progressed to some degree of institutional sophistication and stability, embodying an open and participatory organizational style. Correlated attitudes about sex were evident. So, most strongly, was an ethic and psychology of personal property new to America -- an open one, which seems appropriate to the full society of “post-scarcity” economy whose uncontrolled premonitions now fill the houses of the middle class and excite our imaginations. (12)

To some extent, all these values and phenomena seem to characterize every revolutionary context or process displayed in our Western history, despite the constraining influences of particular ideologies.

Fourth: The birth of revolution is glorious and noted for personal transformation: in it prostitutes turn pure. The Haight, like the FSM, was a rich and mobile environment of free expression, of mutual interaction and need. For a while, its energies were not focused to do immediate battle; and its internal social climate was even more nourishing, and incredibly tolerant and patient. Such a context is intimately therapeutic.

The Haight was a concentrated laboratory for the process at work in America's young, which may be seen as the therapeutic reconstruction of individual personality in a simultaneously developing social matrix. (13) The clearest examples -- which I believe to be extreme versions of typical individual processes -- involved the recovery, re-integration, and therapeutic growth, in communes, of personalities whom LSD experiences had pulled over the edge of what we inadequately describe as psychotic breaks. In a process inextricably involved with the evolution of its context, I saw such persons rebuild and build newly their selves with relative degrees of rapidity, humaneness, and completeness, for which nothing in my previous experience -- neither example nor rumor -- had prepared me.

I imagine the "success" ratio, however you measure it, was not very high. Surely it dropped as the young community grew paranoid, strained, and swamped, before its therapeutic lore was well developed. Even so, I saw enough. I do not believe that the clumsy, fragmenting operations of our specialists and specialized institutions match the present effectiveness of such total-context therapy, let alone its potential.

I will return to the question of what skills and factors are involved in such reconstruction, but several are familiar already. Examples of successful change in process provide ratification and encouragement. Without a strong concept of deviant behavior expressed in a punitive social framework, fear is dramatically reduced. Trust is an all-important variable, as is the supportiveness of the context. The tolerance of the Haight was not simply neutral, but often active: at its best, it led people to encounter and engage with all that was strange, including the brokenness of their brothers and sisters.

Certainly the Haight held a highly selected (though diverse) population. Their psychological profiles resembled those of the FSM arrestees, who as a large group tested out with unprecedentedly high scores in a cluster of variables centrally involved with free learning ability: autonomy, impulse-expression, fantasy-freedom, and others that contribute to the psychological aggressiveness and openness characteristic of good learners.

Are more general populations capable of undergoing such processes of learning as those described here? Can they deal even this minimally-well with the experiences and tools of open forms? Much evidence suggests that they can. The opening of space is a recursive activity now progressing in a favorable climate of historical potential. Minds blown by the FSM came to the Haight; and the instant televised images of both blew further minds across America, opening the universe of the possible. It is now clear that these two events represented the leading edge of a massive motion among the young, and that the technologies of change, which prepared their participants, have been operating throughout America with effects that are only now beginning to become apparent and are still accelerating.

The Berkeley Switchboard

A compact example of the reconstitution of authority in open space appeared in the interior organizing process of the Berkeley Switchboard, a standard hip community-service agency coordinating housing and transportation, providing medical and legal aid, and so on, for one of the Haight's sister communities. Sponsored by the Free Church -- an experimental ministry itself sponsored with few expectations by a collection of liberal groups and churches -- the Berkeley Switchboard's organizers were given free space in the form of a house and being left to invent their own thing.

Their constraints were operational goals: to achieve a stable internal society, which left its members free to create and coordinate their work. The style of this micro-society necessarily had to be that of the democratic commune or extended family which the larger community is evolving as its distinctive experimental life-module, often with a specialized work-orientation. In this example, the work was central, constantly evolving ,and therapeutic (the changing learning to help the changing change), which may be why some aspects of openness characteristic of this form show up most extremely here. The Switchboard had to organize itself around a constant flow of visitors and new members and major turnovers in its work functions and force -- and around persons who were freaks learning to work while freaking freely, who like as not would file cards while stoned on acid.

Sleeping bags, filing cabinets and freaks invaded an open space, graced by the attitudes of the Haight. At first there were simply no rules. In a voluntary behavioral Chaos, people lived and worked as they pleased, and invented elementary forms of cooperation. Services struggled into being. Garbage piled in the kitchen and collected rats. Drunken bikers beat itinerant hippies with chains in the living room.

After it became sufficiently clear that such phenomena seriously hampered the Switchboard's work, rules were instituted, bearing the authority of their self-conscious and public creation, and backed by ostracism and physical force. Such creations were difficult and instructive for a community deliberately oriented toward tolerance and non-violence.

Compassionate hospitality led them to open the place as a crash pad; a glut of transients closed space, and they had to learn to restrict the numbers without closing their doors. The Switchboard's people dealt constantly with this problem of developing appropriate limits on the free expression of their natural energies and impulses: limits that would not cause these to wither, but would permit them to flourish in a total social ecology.

The community's distrust of the Authority Complex and its reluctance to legislate helped create an environment in which rules and social norms were devised only when collectively felt to be absolutely necessary for survival and function. Such rules came about in response to specific and mutually recognized problems. They were tailored to suit the society's immediate nature and needs and -- in this high-feedback and participatory environment -- were constantly open to challenge and revision. Their governing aesthetic was that of minimal constraint consistent with operational goals.

Here the process was elegantly displayed; but this style of reconstituting authority is visible in each of the learning-environments described above. To build successfully in such open spaces requires in individuals not only the ability to tolerate and experience intense expressions of emotion, but also the ability to generate and deal with high and rapidly changing flows of social and personal energy. They must also be able to maintain themselves and function within the ambiguity and anxiety, the tensions and fears of partial social and psychological chaos. In large degree, the appropriateness of what they build will be proportional to their ability to sustain these dissonances and endure these stresses.

A critical question, then, is how are these abilities developed and improved? The most general answer is as important as it is simple: by practice, by a progressive sequence of relatively successful exercises. (The importance of such monotonic chains of experience in developing new behavior, within whatever framework of reward and failure, is well known throughout learning theory, beginning with the rat-running level of simple conditioning.)

From this perspective, most of the learning events described above are seen to be models of typical environments that depend on and nourish these abilities. Their historical progression occurred around some actual continuity of individuals -- though its implications and echoes are now nationwide -- and furnishes a partial and parallel recapitulation of the process of the development of these abilities within individuals. All of these learning forms -- from confrontation politics to therapeutic community -- are reproducible technologies and are re-usable in varying degrees and adaptations. They are coming into wide use.

Formal Educational Forms

Before continuing on the question of what tools develop the psychological skills necessary to change, I want to deal with some institutional environments of free learning that exhibit what is built in open space.

The Tussman Program

The Experimental Collegiate Program of the University of California at Berkeley -- informally called the Tussman Program, after its organizer -- began in Fall 1965, in the open space of a former fraternity house. The two-year program included 150 freshmen, and a faculty of five professors and five advanced graduate students, drawn from many disciplines. The formal curriculum each term consisted of intensive non-disciplinary study of a small core of readings drawn from a major epoch of cultural change, with three scheduled lecture/seminar hours and one paper each week. This, and the expected extensive informal interactions, accounted for four-fifths of the students' class load. The Program's plans were at best sketchy; it hoped to develop them in the process of evolving into a self-governing community.

In several senses, then, the Program was an open space. Its first years furnished a compact, luminous example of the crippled growth of free learning in the live but partial presence of the Authority Complex; and of the territorial competition between the two.

Real needs are revealed in open space. Entering a program explicitly promised to be theirs to help construct, the students tried to make it responsive to what they saw as their immediate needs, both personal and social. These may be symbolized by -- but were by no means limited to -- their needs to deal with psychedelic drugs and the War, felt most intensely in the current climate of Berkeley. In each case, the tasks were to choose some action or relation to the problem, to encounter and deal with its personal consequences, and to interact with others variously involved in this process. But drugs and the War played at most a peripheral part in the lives of the senior faculty. The professors were not interested in revising their conception of the Program to make these concerns central, and resisted attempts at this -- even when these concerns related directly to the studies of the program (e.g., concerning the Greek Oracles.)

The difficulties in implementing these needs were reflected in the Program by internal political struggle. This was largely concerned with educational governance: with the questions -- which at first seemed genuinely open -- of how and by whom the curriculum and its styles were to be shaped and implemented, and faculty chosen and retained. By the year's end, the answers were clear: the students had no formal say or effective power in these matters. The governing group was not open, and it came to be rigidly restricted to the senior faculty. (Even within their small ranks, the only stable mode of power and decision they could evolve was not communal or consensual but autocratic, operating in the classic style of the Authority Complex.)

Despite this, within the actual space of the Program, authority was heavily divided and conflicting in interest and style. This tension was maintained largely through the teaching assistants, who accounted for most of the direct student/faculty contact. In them overlapped the authority of their nominal roles, to which the students responded from deep conditioning; and the opposed and freeing authority of their examples as persons whose condition was close to that of the students, and who were struggling visibly with the same sorts of problems.

Whether personal or social, space in which conflicting forces and styles of governance struggle is electric with social and psychological dissonance. (14) Such fractured authority is typical of incoherent open space (coherent open systems are a different and Utopian matter, though these notes are meant as a guide toward their construction). Such space is fertile for growth, provided that most of the available energy is not bound rigidly into the conflict but can be disposed in a flexible and appropriate balance between the requirements of growth and the development of an internal framework of authority that will prermit and support it.

In the Program's case, the students' "academic" and other learning was on the whole adequate and often considerable, as measured by both the system's standards and their own; and they shared an intense and painful laboratory in the struggle of freedom and authority. But too much energy was in fact bound into the unsuccessful conflict and its immediate demands, and their knowledge, skills, and will were undeveloped. The students were unable to reconstruct an effective, collective authority of a different form from that of the Authority Complex.

Before its power, their concerns retreated into scattered private work, and the Program's human space became frozen in a permanent and standard division. One territory was public, common, and institutional; in it the Authority Complex held unchallenged sway, which was achieved and symbolized by firing the teaching assistants at the first year's end and eliminating them from the design of the Program and its successors. In the other territory, among a scattered community with no effective group structure, the students tried to deal privately with those needs for change and learning which the Program no longer held the possibility of satisfying.

This ultimate territorial partition was reflected early on by a tendency among the students to divide into two fairly-sharply defined groups, determined not so much by what they needed to learn as by the styles of learning for which they had been prepared. The Program's internal process forced and clarified this division. One group did not choose to try, and generally were badly able, to function outside of an authority-centered learning framework. (15) Though the others were not successful in establishing a collective alternate framework, as individuals they were distinctly more sure in their self-directed learning skills, and better able to deal with the anxieties, dissonances, conflicts, and emotions of the free-learning process within the Program's society. In these and other skills, the students' unperturbed self-evaluations were generalIy accurate -- a general truth that points to the importance of building change-systems that depend on the conscious self-selection of their participants and allow them maximal self-direction.

The contrast between authority-directed and self-generated behavior appears in every partially open space. In group interaction, as the politics of situation unfold, people sort out into subgroups that reflect these tendencies. Yet both tendencies inhabit each person in some unique balance -- as if this one were 30/70, and that one 60/40. This private balance is not fixed, nor are the characters of the social roles one plays determined entirely by it. Both change in response to the need of the social drama for players to fit its roles, so that he who would be a rebel in Sparta might be a tyrant in Athens, as many members of the Program found.

On the social or the personal level, this division escalates into polarized conflict whenever the context is not rich enough to satisfy both sets of needs; for a learning environment that refuses support is as tyrannical as one with no doors to freedom, and makes people as panicky. The polarization along psychological capacities and orientation split the Program's staff -- not entirely along lines of age, a hopeful sign. Most of the professors -- the Program's head, in particular -- were unable to endure the chaos and emotions necessary either to build within the Program a structure of governance and learning that the students felt dealt with their major needs, or even to engage with much intimacy or effectiveness with individuals around matters the students felt not to be peripheral.

True, the professors' experiences was deeply different from those of the students and had not developed in most of them the necessary skills. But beyond this, they were simply, deeply, and humanly terrified: of Chaos, of contact, of the anxieties of freedom and building newly, of the unknown depths and content all significant learning must involve -- the eternal terror in response to which Hobbes articulated the political theory of the Authoritarian State.

In this case, no social mechanisms developed to deal therapeutically with the terror, which instead was intensified by the Program's process. Both sorts of students came to feel themselves adrift and unsupported. The professors reacted classically, by closing whatever was open. Some acted this out by reinventing and restricting office hours and minimizing contact with students; by firing the teaching assistants, whose presence forced real contact with another reality; and even by literally fainting again and again. Mostly, they came increasingly to define their self-interest negatively, as the prevention of the destruction of their personal and social authorities. The remedy was to reassert total control wherever possible and to avoid the space outside this domain. To this they applied their energies successfully. Authority in the Program was tightened along unreconstructedly Hobbesian lines, in practice and in conscious theory. Despite its exterior features of newness, the Program collapsed toward a standard learning form, fragmenting and familiar in its process and consequences.

It is worth mentioning that the key professors involved in the Program's failure were noted and active political liberals: its head was a well-known exponent of civil liberties and responsibilities, another was a prominent member of a progressive school board, and another a constitutional lawyer in behalf of radical causes. The process of their attempts and failures to deal with the problems involved in creating a major new learning environment is typical, in outline and in detail, of a wide variety of related attempts by their peers. (16) Clearly, any style of educating has its own conjugate politics. The political knowledge and sensibilities of the American mainstream -- including in particular the Liberal current generally reflected in our present formal systems of education -- are simply not adequate to the problem of constructing on any human level systems of free learning.

The Teach-In

Properly, an analytic catalogue of my generation's new learning forms should deal with the Teach-In, the first example of which was the Vietnam Teach-In at the University of Michigan in 1965. As a way of creating and structuring space for learning energies. teach-ins can be understood as intermediate between the models of the Tussman Program and the free university.

The Free University

What happens when the needs, orientations, and energies that were absorbed and distorted by struggle within the Tussman Program find a more genuinely open space? What first forms evolve naturally? Their ideal modular unit has been described above as a free learning group. Such units typically exist within a larger institutional form, visible in the hundreds of free universities and student-generated experimental colleges that have sprouted on campuses and around free youth ghettos.

Almost all campus-based free universities come to involve some 6 to 10 percent of the students -- indicating a class of persons psychologically predisposed to experiment with the content and process of learning. Yet the constancy of this proportion, from working-class state schools to private elite universities, implies equally that such personal readiness to experiment comes about in response to objective social conditions and the potential for collective experiment -- again, as if a chance to play a new social role drew forth the players. Given this fraction's involvements in politics, drugs, etc. (as reflected in Free U curricula), the figure of 6 to 10 percent provides a rough estimate of the fraction of (white) college youth willing to venture the edge of social change on an ongoing basis.

The first successful Free U was begun by San Francisco State College students in 1965. Three older students grew tired of grousing about the school and went down to Registration to hang out and gather volunteer groups of freshmen to talk about their education together. After a semester, some members created an interdisciplinary course for their general credits, with cooperative professors; in several years this evolved into a General Ed study group to design and implement major changes in San Francisco State's undergraduate requirements. Other members set about organizing more classes for whatever people wanted to learn. The next semester began with seventeen student-generated experimental classes, which soon banded together to form the Experimental College. Two years later, the carnival multiplication of learning groups involved 2,000 students, and the E.C. was discovered by the media and echoed in East Lansing.

The original organizers of the E.C. developed and analyzed a distinctive style of catalyzing change. Generally in our culture, the unit of change is conceived as a homogeneous mass population, like an economic or Economics class, to whom a rhetorical appeal is made, in the name of History, Learning, or whatever, urging appropriate change. (When possible, the rhetoric is backed by force.) This model describes equally the teacher lecturing, the style of the American Left of the thirties, and the social and economic legislation of the Johnson Administration.

In the contrasting model of the E.C., change is catalyzed by creating a climate of small, autonomous groups engaged in satisfying activities that generate the energy for them to go on. Change is stimulated more by building and exhibiting actual working examples than by trying directly to influence the whole of a large population. The presence of such new examples is, technically speaking, a mind-blower; that is, it breaks expectations as to what forms of personal and institutional behavior and reward are possible. In this expanded universe of possibility, those with available energy and skills can go about constructing their own examples: not in imitation, but after and out of their own sense of needs. Drawing attention to new examples is no problem, for the spectacle of people engaging in genuinely satisfying activity is rare enough that the vibes this generates are picked up by those who are ready to move. (17)

On an intimate scale, this model describes the catalytic mechanism of leadership in small free-learning groups (compare "Qualities of a New Style" in Chap. III). It also describes the multiplication of functional groups within the FSM and the Haight. On a broader social scale, it accounts for the almost instant reproduction across America of the examples of the FSM, KMPX, the Haight, rock dances and be-ins, communes, Switchboards, and free universities. On these two scales, the role of mass media in spreading examples is essential and deserves careful study in view of the way the mass media market false expectations along with real news. (18)

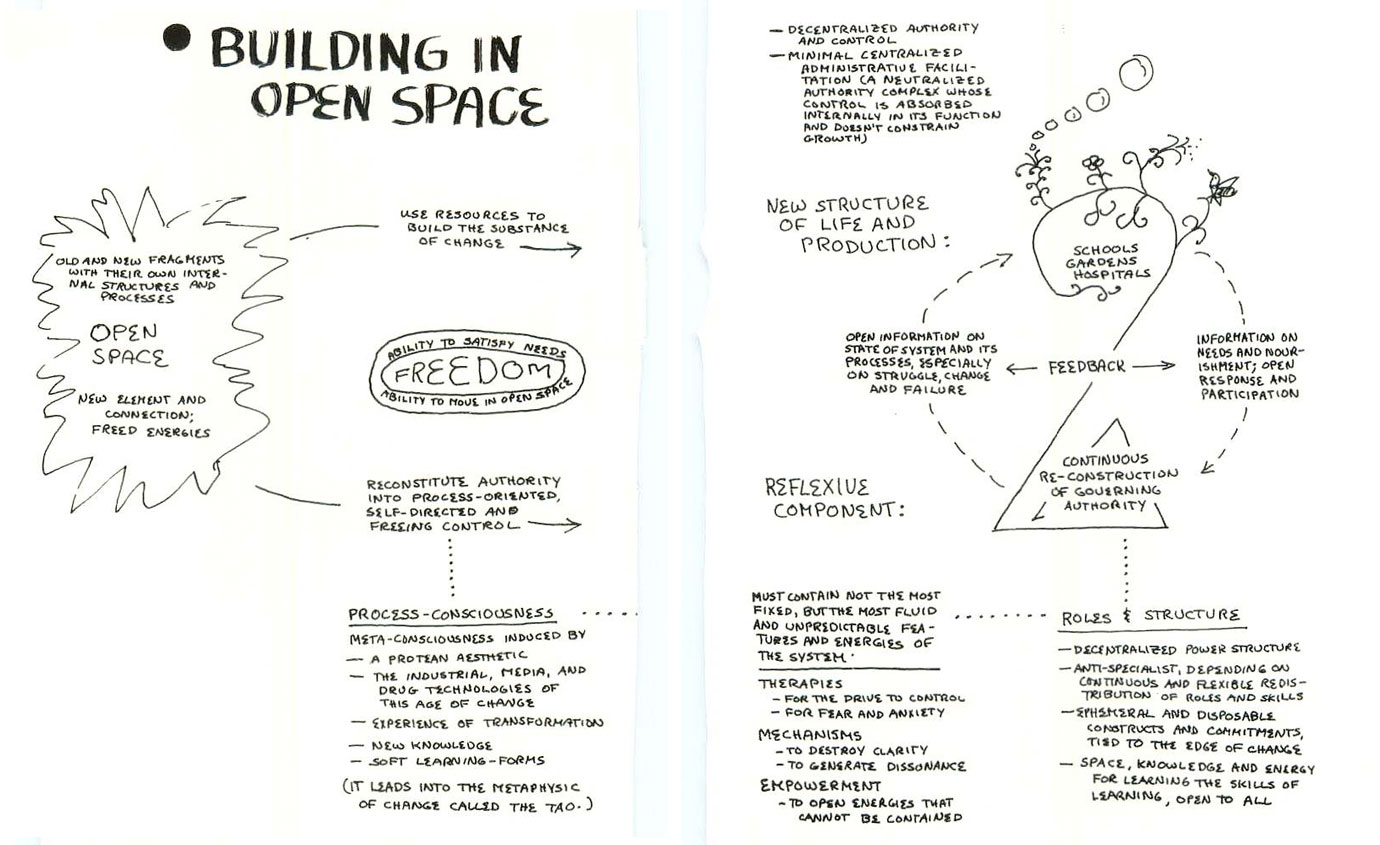

Organizing processes of this sort -- i.e., that propagate real examples by media and direct contact among people ready to move -- catalyze growth that is sudden, simultaneous, and deeply decentralized in that its forms and standards fall under no central control, not even an aesthetic one. (Consider the case of rock music.) The institutional form compatible with this free organizing process has a structure with decentralized editorial control and centralized administrative facilitation. (19) (Contrast the music industry.)

The clearest example of this form is the free university, a cooperative association of voluntary learning groups investigating a broad curriculum in a variety of old and new styles. Typically, the groups are completely autonomous within the institution they form, which is governed by a decision-making group open to all who wish to participate. Such a form can operate with gratifying success, as in the case of the E.C., which not only flourished in its classes, but was able to execute an open-ended series of major organizational restructurings over several years, each time strengthening group growth and opening new space.

This capacity was the product of deliberate design. The E.C.'s organizers set out to develop an institutional mode that would prove flexible to change, able to modify its nature to suit its discovered needs. The ongoing conversation responsible for this development also elaborated the model of a free learning group described above, of which it was itself a remarkably successful example. A collection of autonomous experimenters engaged in evolving fluid cooperation, and beyond them the Experimental College itself, functioned as a laboratory that tested its theories on, and applied its understandings to, its own shape and workings. Thus, like a model conversation, the core group became not only a focus for research and propagation but also its own product and end.

This operation of the E.C.'s core group within the larger form is a clear example of a reflexive institution, containing within itself explicit mechanisms for consciously examining the state and process of its growth, and for changing itself in response to this learning. The institutions of our present culture are all petrifications of the Authority Complex; their reflexive mechanisms work ineffectively when they even exist. But in order even to survive in this age of accelerating and chronic change, which dramatically exposes Man's condition as the active and involuntary creator of the changes of his being, all human institutions will in some sense have to include functional mechanisms for their own continual change. (20) This holds true on the small-group level, as in large institutional forms, and also within the interior, personal space of each changing man and woman. On all three levels, these mechanisms are analogous. They center on the consciousness of process and its deliberate manipulation. In the case of the small group, the reflexive mechanism is visible not structurally but in its operation -- as a set of roles and rituals for bringing group energy to focus on problems with process.

In the case of the E.C., several institutional processes overlapped to make the reflexive mechanism highly visible. The E.C. was a natural host for groups learning together about educational change; and these groups in turn generally contained the people who were instrumental in shaping the E.C.'s form and growth, who formed its ongoing organizing core, and who studied it within itself. Often they even received class credits within the formal parent institution for their study and organizing work. Thus the reflexive mechanism of change existed as a model sub-unit of the E.C.: unique only in its function, typical in its interior form and process and its nourishment by the larger structure.

It is crucial to note that this reflexive core group was neither a study group nor an element of a check-and-balance system. It was empowered, in part because its membership overlapped with that of other change-seeking subgroups, to open all of the system's energies into self-directed change. And it was open to active participation by anyone. (The contrast with the standard mechanism of change in American colleges is immediate and deadly.)

Beyond this, the general conversation about structural and educational change in the larger institution -- San Francisco State College itself -- came to be visible, centered, and organized as such in the Experimental College. The conversation was strong, well organized, and implemented with political skills which had been developing for six years within a climate moderately favorable to institutional change. Consequences included the design of a new student center and the complete revamping of the school's general education requirement, both accomplished totally within the E.C.; and a general loosening and revitalization of San Francisco State's curriculum, and of the process for instituting and crediting study within it.

The Experimental College was in part deliberately conceived as an experiment to develop a multi-phasic agency of institutional change within the larger institution, capable of whatever thought and action were appropriate. On this broader scale, we see again the successful operation of a reflexive form.

The main skills involved in the E.C.'s reflexive success were those of political consciousness. They were developed by learning the structure of power -- on all institutional levels -- and how to manipulate it.

Considerable open space was generated by a style of moving which aimed at avoiding a polarization of the environment's energies into opposed and paralyzed forces, frozen in conflict and expectations, and tried instead to make visible common areas of self-interest on which parties could begin to move cooperatively. In interaction with faculty and administrators, students upset expectations by not adapting the confrontationist postures currently expected of activists, and by initiating and making visible bodies of serious work. The E.C. itself, not being clearly either within or without the larger college, had an ambiguous institutional identity which confused expectation and response, opening further space.

These open territories began closing as soon as new growth reached a point where irreconcilable conflicts of interest were clearly revealed, as seems to be the general rule. In this case, open conflict began when the E.C. and the larger college contended for scarce physical space for their expansions; and when the E.C.'s styles and content began to make ponderable demands for space and credit within the larger institution, and thus for significant change in its forms and processes. Later, black and white student political movements -- in whose generation and nurture the E.C. had been critically involved -- were directed against the college itself, demanding massive changes, and by early 1969 San Francisco State became the battleground of the country's longest continuous student strike, largely around issues of affirmative action. The space of ambiguous identities closed quickly and permanently; and further building at San Francisco State occurred only in space pried open by the leverage of painfully cultivated skills and power. These were inadequate to preserve the Experimental College. After Governor Reagan appointed Hayakawa as Occupying Authority, control tightened, student funds and official sanctions were withheld from the E.C., and it finally died.

The Experimental College had a typical free university curriculum. Its subjects of study were mostly change-oriented: the perspectives and skills of social change, the skills of small-group interaction and the learning process, tools and workshops in various species of personal encounter and therapy. (Most of the remaining courses dealt with the products and production of a new culture.) The curriculum's methods were innovative and generally therapeutic, and were often explicitly designed to this end.

In liberated territory, guerrillas build hospitals and schools to care for the needs of their people, and factories for the machinery of the wars of hunger and freedom. The metaphor holds in rich detail. Understood broadly, it describes the creation of open space in territory and among people dominated by the imperialism of the Authority Complex; it understands what is built in that space, and why; it prescribes strategies for simultaneous struggle and growth on all human levels, for extending the space and that building.

Psychedelic Experience

From social forms to the human interior is no long journey. The sweet smell of grass will take you there from corridors and rooms wherever the young are learning. For the "psyche-expanding" drugs -- marijuana (grass), lysergic diethylamide acid (LSD or "acid"), and related chemical agents -- along with confrontation politics and a new music have provided the most intense learning experiences shared by large numbers of the young.

By 1969, perhaps one and a half million had dropped acid, and ten times that number used grass regularly. I class these drugs together because their immediate effects are similar in essence, though grossly different in scale, and their cumulative effects are comparable on both counts. Like Ac'cent (MSG). the psychedelics are a colorless, tasteless spice that heightens the flavor of whatever is cooking in the personal and social stewpot. They bring out and accelerate whatever change is going on, good and bad, in all its contradictions; and the deliberate will can use them to fix and extend what changes it will.

The surface parallels between psychedelic experience and participation in free learning groups, especially those oriented toward encounter and therapy, are immediate. Both result in a "high" or "stoned" condition, characterized by heightened inter- and intra-personal openness, and by a sensation of containing and being embedded in higher flows of psychic energy. The more often one has these experiences, within broad limits, the more permanently “high” one can become -- with the aid of other disciplines to preserve their breakthroughs -- and the more able to use contact with any source of live psychic energy to generate and sustain the high condition. (In drug culture, this phenomenon is called "contact high.") At first one just sits there stoned: dazzled and reveling in the perceptions, the sensations, and the energy flows, encountering the emotions these arouse. Then one begins to learn how to deal with the flow: it becomes a tool whose various colorations and powers are open to exploration. Successful experiences develop a greater sense of control within and upon these energies, wherever control is possible and appropriate.

But the parallels run deeper. For group learning, like all human change, is a cyclic process of breaking established patterns to create open space in which new ones are formed, and the psychedelic experience gives basic insight into some of its key features. The mind construes the reality of experience, and patterns are its image. To break open cognitive or social patterns is to break open simultaneously the minds that project their coherence. Thus the adverb often used to describe the psychedelic experience -- mindblowing -- will serve well to name the first process of the cyclic paradigm. Aldous Huxley spoke of the experience as “opening the doors of perception.” Into the house of the mind comes knowledge that transcends its immediate system. (21) This phenomenon of transcendence is responsible for the intimate and age-old association of psychedelic drugs with mystical insight and religious culture. For the purpose of our analysis, however, the knowledge is of needs, existences, resources, and potentialities not previously realized. (The skills and meta-skills of free learning are grounded in consciousness of these things -- see pertinent sections of Chapt. III.) Such new knowledge does not simply extend the system it appears within. Within, and ultimately without, the mind creates a new order.

A Digression of Definition

The space of a human system is not a vacuum but a collection of elements, organized by functional relationships or interconnections into a form. The space and form are closed insofar as new elements and interconnections are predetermined, and open insofar as they are not. Free learning is the organizing of form in open space: it generates new varieties of form, relationship, and element. Organizing in closed space is something else again: here form changes its scope but not its nature. Space fully organized by the style of the Authority Complex is only one possible variety of fully closed space (others may be less pernicious). Space governed partly by the Authority Complex and partly by another mode is incoherent, and open to the extent that the two organize there in live conflict.

Such abstract concepts provide a frame for any level of social reality. Some examples:

(1) Your consciousness is a tissue generated from experience: elements of perception are connected and these connections built into higher order. In our culture, most of these connections are causal: if this, then that: [(A--> B) and (B-->C)]--> (A-->C)], following the logic of hierarchy. To a great extent, you choose not to admit into your space elements and connections that do not fit your categories. Even so, you know what incoherence feels like.

(2) Consider a group of people, A, B, C ... They are elements of the group's space, as are their extensions -- their cars, houses, productive technologies. A and B are in love, etc.; A and C argue politics, etc. These are connections, <AB> and <AC>. But <AB> and <AC> are also elements, for in the process of the group these relationships may themselves be functionally connected: one factor of <<AB><AC>> may be the way <AC> draws off anger from <AB>; and so on. Now the group gets a new member, Z. Is its enlarged space more open? Probably not, if it's a business firm and Z is a secretary (though there's always some chance Z will seduce the management into turning production to new priorities). But if the group is a white commune and Z is black or a physician who can teach people to heal each other, the space opens.

(3) Recently, the whole of human space has opened into radical incoherence by the appearance within it of new elements -- qualitatively new means of production, which open the possibility of new relationships of every sort. In this space two principles of organizing contend. (22) All the examples in this chapter may be understood as experiments in shifting the balance between them.

Back to the Track

The psychedelics enrich individual perceptual space with new elements and new connections. Neglected or repressed sensory and emotional experiences and memories reassert themselves, often abruptly, and new varieties become immediately accessible, sometimes by seeing old ones in newly reflected light. What springs into consciousness is partly what already presses to enter; in this, selection is a function of the mind's immediate state and needs. But in significant part, selection seems to be truly open and random. Both the emotional relevance and the unpredictability of what appears in the opened space are the principal triggers of the fear that characterizes this -- as any other -- learning experience, and leads people either to avoid it or to freeze within it, unable to deal with its demands and possibilities.