IX.

Activism at Mainstream U

and the Organizing of Counter-Community

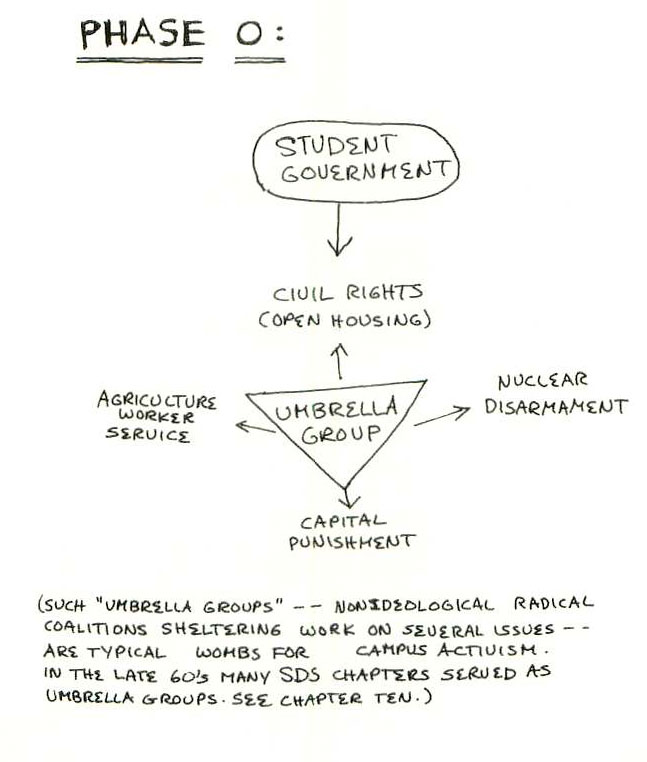

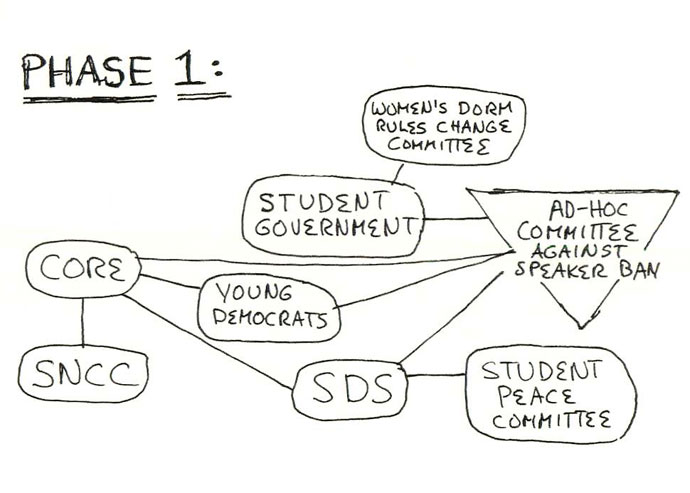

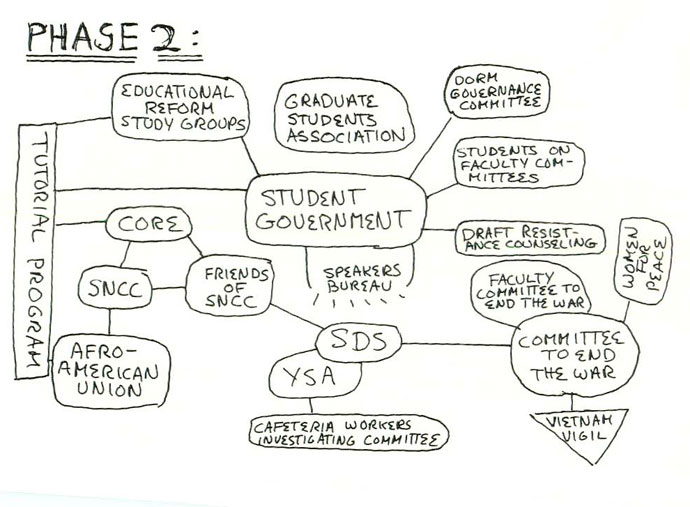

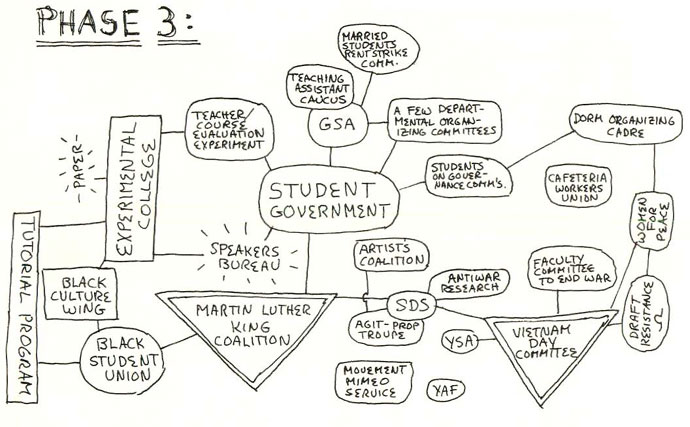

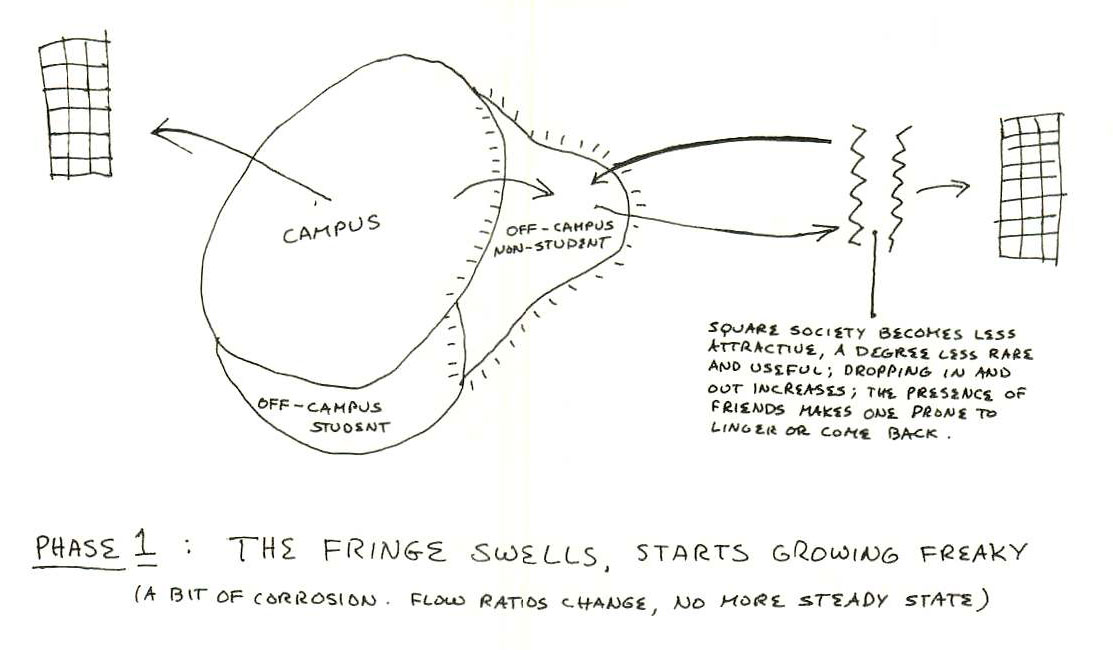

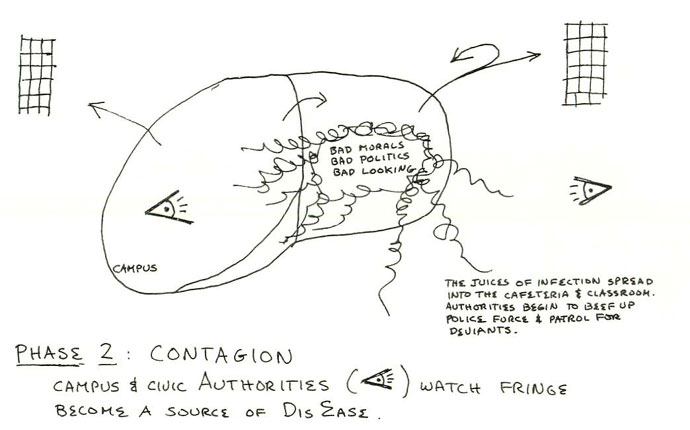

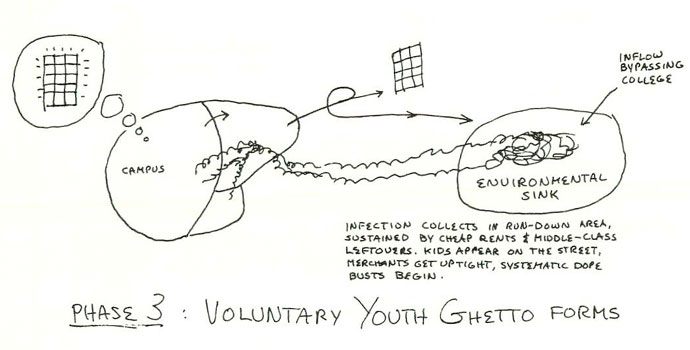

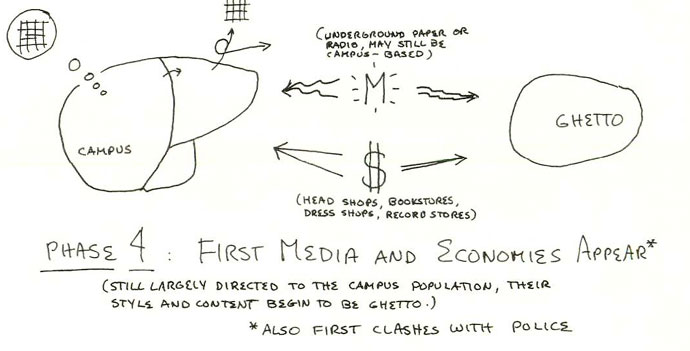

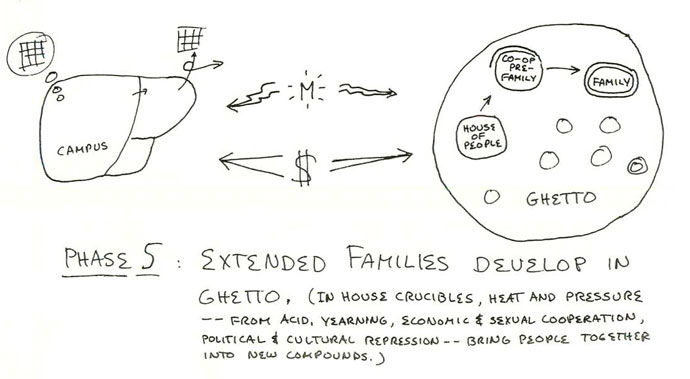

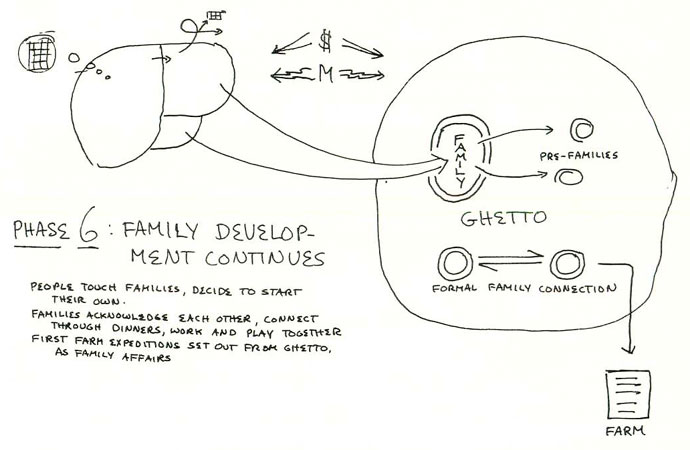

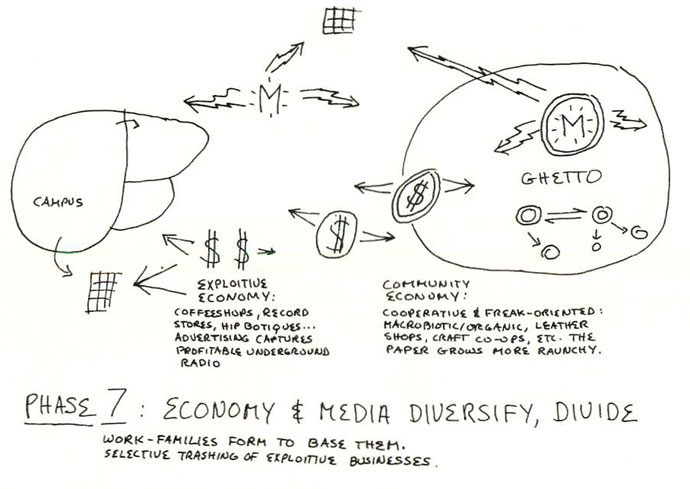

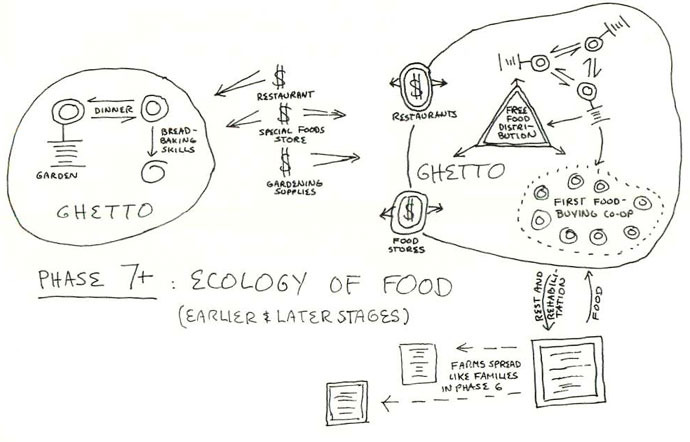

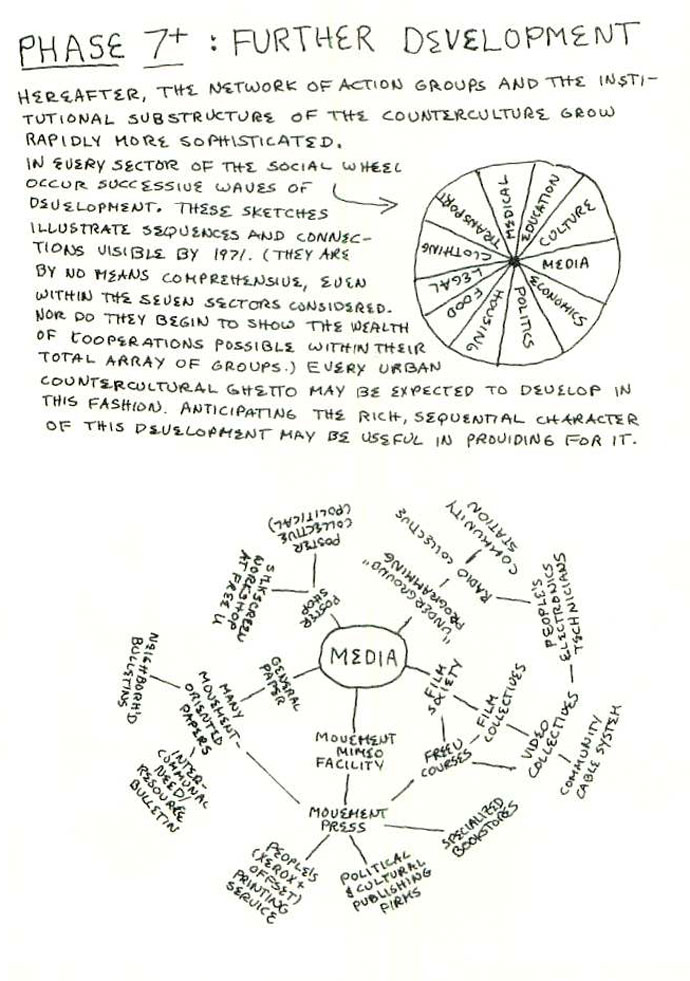

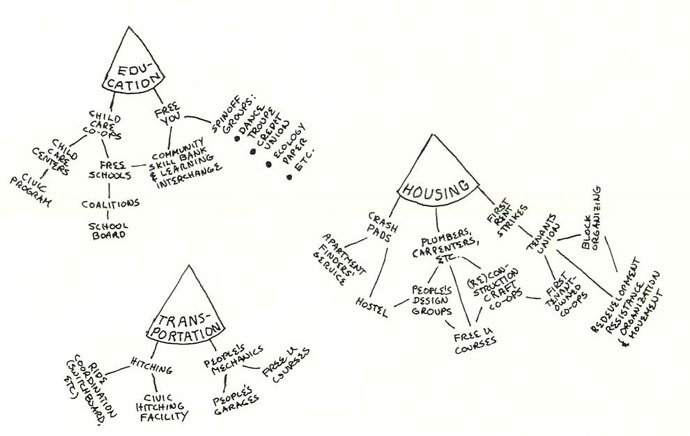

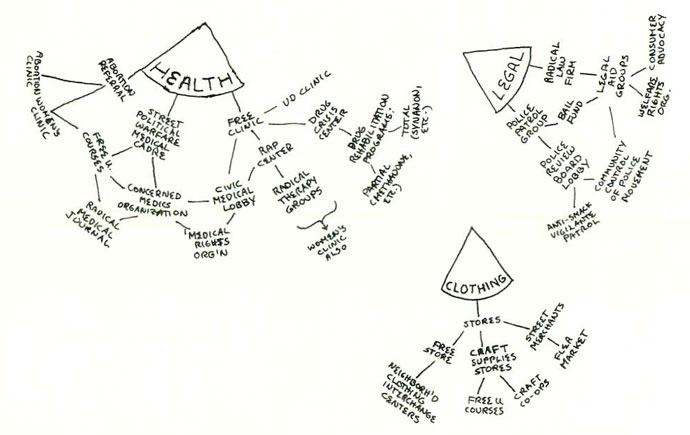

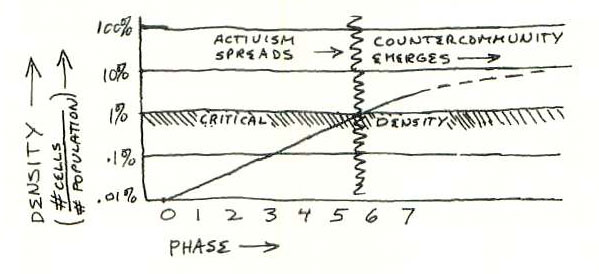

The following diagrams describe typical patterns of evolution of new social energy as it appears in youth communities and is manifested in organized group action.

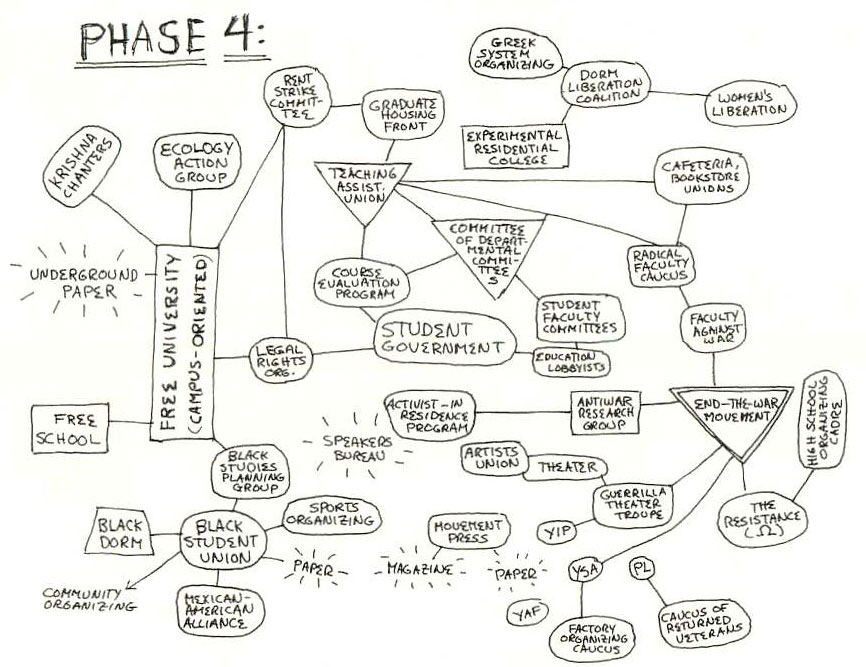

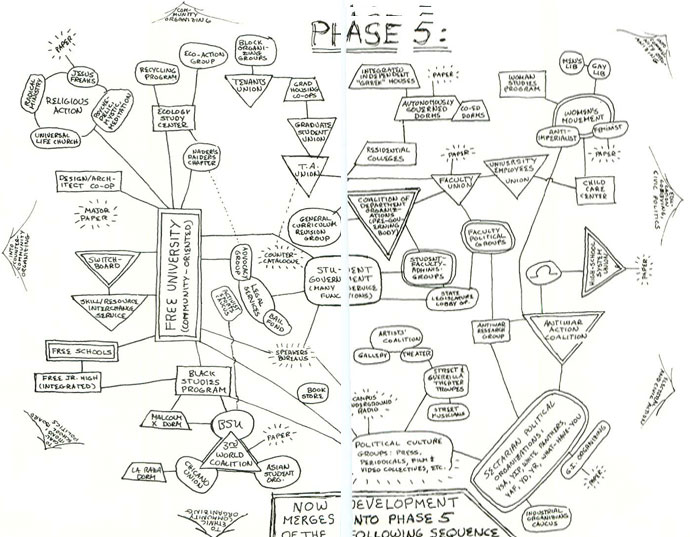

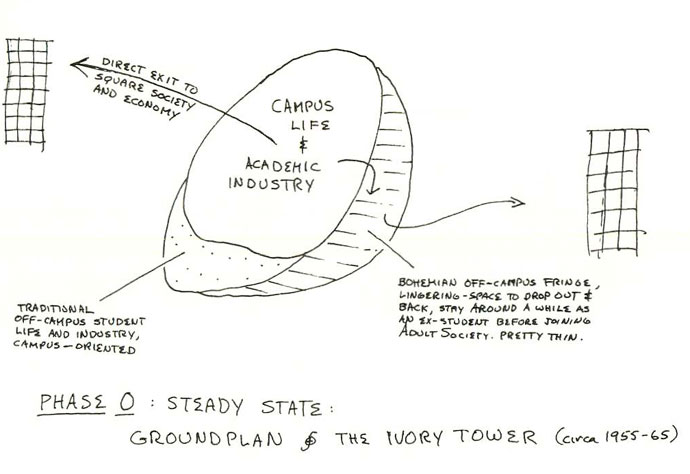

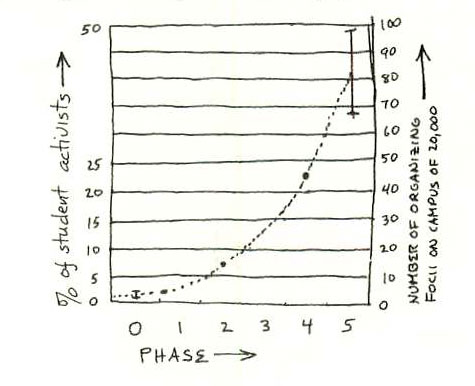

The campus sequence sketches five phases -- covering some five to ten years -- in the spread of activism at Mainstream U, a large state university (upper middle class). The sequence is idealized and might include many more groups; the phases are not sharply defined, and the typical groups of any phase change from year to year. By Phase 5, the range of activities is appropriate to a town or small city, and the thrust of evolution passes into the development of the institutional structure of counter-community (merging with Phase 5 of that developmental sequence). Half the campuses in our nation now demonstrate some version of this model, modified by circumstance and size -- most quite early in the sequence. By 1972, perhaps a hundred major campuses had evolved beyond an (updated) version of Phase 3, and most urban counter-communities could trace their origin to such roots.

====================================================================

====================================================================

====================================================================

====================================================================

====================================================================

====================================================================

====================================================================

====================================================================

====================================================================

====================================================================

====================================================================

====================================================================

====================================================================

====================================================================

====================================================================

====================================================================

====================================================================

====================================================================

Some Observations, Depending on the Diagrams

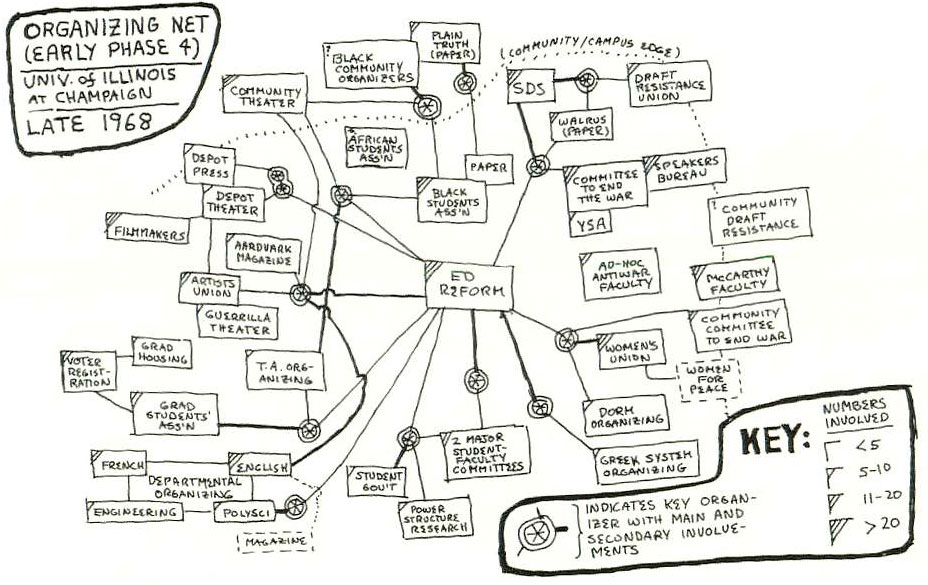

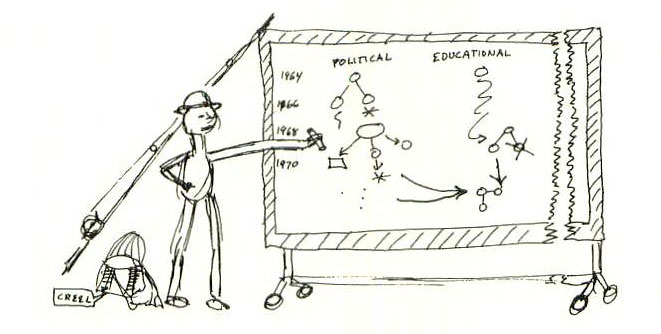

• In the fifth diagram, the school considered is the second-best campus of a better state university system, quartering 30,000 students in an isolated town five times that size. Here its activism is shown, as completely as I could survey it, early in Phase 4 (in 1968), about a year before the student ghetto became conscious of itself as a counter-community and began to turn its energies from the campus into the town.

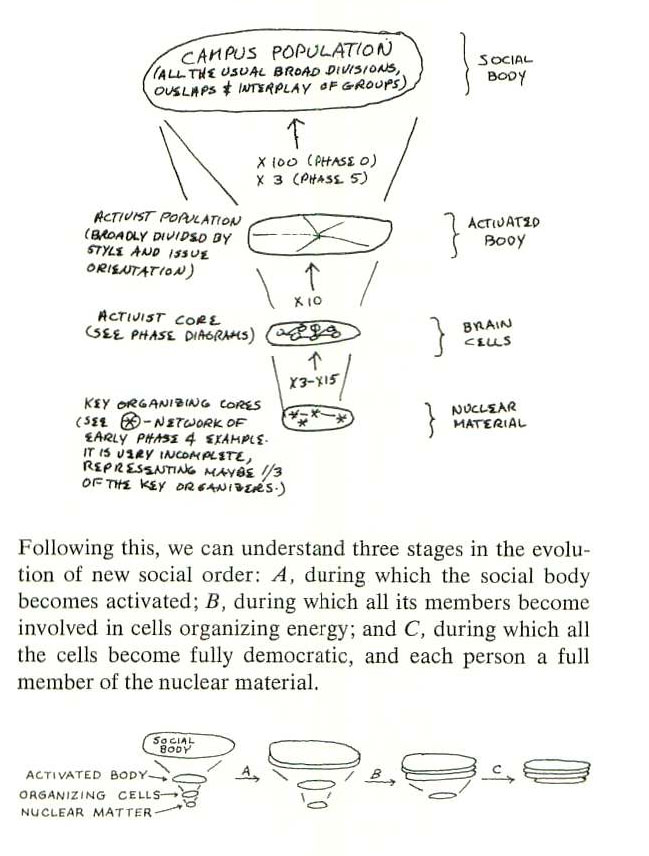

That diagram shows the numbers of persons actively involved in the various foci of campus organizing energy. Some 400 altogether, they constituted the activist core. At this time, about one student in eight was an occasional activist, and one in eight of these was continuously active in the organizing net, i.e . in this activist core. Related proportional figures apply to the other phases; I think they are fairly independent of what particular forms a phase displays in any particular year. Very roughly:

In any phase, the activist core involves roughly one-tenth of the activist population. (What deep constancy is being acted out in this?) This core is a nervous tissue in the campus body, composed of excitable cells connected by overlap or mutual contact. (At any time this tissue also includes several times as many unnamed cells that are more ephemeral and not organizationally visible.) As in animal evolution, raw increase in the number of cells not only permits them to assume more specialized functions but leads them, in the changing environment, to develop into a more complex system capable of more sophisticated functions -- a higher brain directing the organizing of social energy.

• A cell of the activist core generally involves from five to twenty people, and connects some ten times as many occasional activists. When a cell grows larger, its tendency is to divide into interlinked cells of this size. Thus the total number of cells in a campus is about 1 per cent of the number of activists, give or take a factor of two. Hence the "organizing brain" of a small campus in Phase 5 (3,000 students; 1,200 activists) will have about as many cells as that of a large campus in Phase 2 (20,000 students; 1,200 activists), though it will probably be more sophisticated through being better connected within itself. On the other hand, even a very active small campus cannot generate enough core cells to permit the higher orders of brain complexity now visible at some large campuses.

Antioch appears to be an exception to this rule. But for unique historical reasons, it is more nearly a self-governing community than a college. As communities develop, the unnamed cells become organizationally visible and less ephemeral (as in communes). As all social functions come to be organized by this brain, the number of cells, exclusive of simple living groups, approaches 10 percent of the total population (a hundred or so typical cells are shown in Phase 7+ of the sequence of community diagrams above).

• All this suggests the following bizarre speculation. When a certain "critical density" of organizing cells is reached in a population, counter-community consciousness emerges.

While the density is sub-critical, say less than 0.5 per cent, organizing proceeds mostly horizontally, drawing more and more people into activist consciousness. By the time the density reaches 1.0 per cent, one person in ten is in the active core, engaged in building new social form; and the lives of the other nine are directly affected (at least by having friends so engaged). At this point activist consciousness has spread through essentially the whole population, and collective consciousness begins a different order of evolution. Though cells continue to proliferate, approaching their limiting density, the edge of organizing energy turns to the vertical, concentrates on generating higher orders of connection among the cells, and the evolution of a comprehensive and integral society commences in earnest.

• Within each organizing cell there is again -- even in the best of our cooperations -- a key organizing core, generally involving from one person in three (in small cells) to one in fifteen (in larger ones). Call this the nucleus -- or “nuclear material"; for science is coming to a broader understanding of how these functions are served in the cellular ecology -- for it contains the main elements shaping the character and action of the cell, and moderates most communication within the cell and with other cells. Then a crude portrait of the structure and embedding of the organizing brain begins to emerge:

(Of course, these stages are not so strictly sequential as they are pictured here.)

• The "Early Phase 4" diagram begins to display the interconnection of cells in a campus organizing core ("brain"), as this occurs through nuclear organizers. Here the cell called "educational reform" is some eight months old. Growing rapidly, it is about to divide into three or more cells. Yet its space is undifferentiated enough to bring into mutual contact the ten key organizers shown radiating from it -- and through them the twenty other cells in whose nuclei they are involved.

On the Champaign campus, the presence of this open cell enabled a radical increase in the flow of social information among diverse organizing nexuses, which led in turn to a sudden upsurge of activist energy and organization. (Before this time, there had been no arena, other than the bureaucratized one of the student government, in which the various activist tendencies came into intimate contact.) This is one example of the process identified in Chapter IX as centralized administrative facilitation of decentralized activity.

The character of such a social brain depends not only on its size but on the topology of connection and modes of interaction among its cells and among their nuclear matter. A proper academic study would proceed by analyzing these exhaustively for a number of particular case studies. But for us groundlings, involved in building real movements and real communities, diagrams such as these have immediate practical usefulness.

In a number of campuses and counter-communities, I have had this experience: We gather in one room a good number of people from the activist core, including as many nuclear organizers as possible. Setting up a large blackboard and someone to tend it, we conduct a two-stage fishbowl.

In the first stage, a fisherman fishes out what the people know about the developmental history of the organizing they are continuing, and it is assembled on the blackboard, bit by bit. We see the first organizations form, grow, divide, change their names and focus, disappear, diversify. We watch the broad flow of activist energy surface in mass events -- teacher-firing protests, festivals -- and give rise to organization, then subside while resurgence is prepared; we see how antiwar energy, frustrated, expresses itself through ecology for a time; and so on. As key people's names are mentioned repeatedly, we identify successive waves of organizers, see how broadly and long they worked and how they moved on, and whether they helped train others to carry on and transcend their work. When we are fished out, the blackboard records an historical perspective on the present state of the local movement -- a perspective now shared by all those present, enabling all the cells they represent to understand themselves as articulations of a common motion.

In the second stage, the blackboard is reversed, and we concentrate on the present state of the movement. One representative from each cell describes the size and internal organization of the cell and its connections and interactions with other cells. As the information comes out, it is diagrammed; together we watch a sketch of the present brain unfolding. When we're done, we have a rough power-structure analysis of the movement and its communications net. The authoritarian or democratic balance of its system may be understood in the terms of Chapter VII. Usually, the actual sketch shows clearly what parts of the brain are unnecessarily isolated from or subordinate to other parts, and suggests how new cells can be created to decentralize or coordinate the functions of present ones.

Each of these stages takes a long afternoon on a large campus not beyond Phase 3, or in any other organizing pool where the total number of cells is still small enough for almost all to be represented in one room. A richer context requires a group working together for a while -- i.e., the creation of a reflexive cell -- and organized dissemination of its investigation.

(More discussion of this "fishing" process appears in Learning Games.)

Return to: Top | Next | OLSC Contents | Home